There is an old saying in these parts that Boston was built of Bangor lumber and Brewer brick. And it is an easily demonstrable truth. Not only is Boston extant and Maine’s tall timber gone, but Brewer actually lies in a series of hollows left by the excavation of its clayey earth, which was pressed and fired into those bricks which nowadays compose so much of structural Boston. Indeed, as charming a school and athletic field as you can imagine lies in one of these natural amphitheaters.

During the early days of Brewer, brick making was one of this city’s major industries, and “Brewer made brick” was shipped out many miles and had an excellent reputation for quality. We can remember when the “brickyard flats”; where bricks were spread to dry after being “burned” or baked, made excellent baseball diamonds when not covered with drying brick. In fact, the last brickyard in Brewer, Brooks brick Yard, stopped making bricks in 1956, and since that time, the Brooks Brick Company has operated as brokers, importing bricks from brick makers in Maine, Massachusetts, Ohio, and other states, as well as Canada.

So let’s get to Brewer brick making from the start.

Some of the geographical contours of Brewer can be traced directly to the days when brick making was a very important industry. The working of these yards, one authority says that they were twenty at one time, caused the cutting away of many hills. One notable example of this is The Bucksport Branch of the Maine Central railroad. The tracks follow these cuts from Main to Jordan Streets. The Athletic Field and the Auditorium are located on the site of an abandoned brickyard, believed to be John Holyoke’s. We also find a Dunn’s brickyard mentioned, and a brickyard on the Farrington farm.

Several of Brewer’s early industries cooperated to make a fine vessel load for shipping. Lumber was stowed below deck with the brick on top of that. Then the bales of hay were loaded on top of the brick and the whole thing was covered with canvas to protect it from the weather. Ships carrying these articles as cargo , brought back coal , pig iron, and cement.

It is documented that at one time seventeen brickyards used 3000 cords of wood a year. The brick making season was generally from May to September. One Mr. Holyoke, who owned a brick yard, stated that if he began at the earliest point, he could make the first ready by July. In Maine, the brick export business was at its peak in the early 1850s. The Civil War checked the business for a number of years, but business picked up again until the 1880s.

Of the number of bricks burnt at one time, which was between 250,000and 900,000, only about one percent were found to be unsalable. Usually, seven men were employed steadily, with extra help called in when it was needed. The men worked from 5AM to 7PM, with the necessary amount of time allowed for three meals. Many Irish laborers were employed in the brickyards. It took about nine days for a burn to be completed. We remember the active days of the Brooks Brick Company, when a red glow in the sky would strike terror in the heart, to be relieved almost immediately when we realized it was only the burning of the kiln.

Water for making brick was taken from a small brook near the Holyoke Brick Yard. This yard used about 2000 gallons of water a day. This brook has become part of the City’s sewer system, and cannot be seen today.

An item, dated February 12, 1900 states that on a Saturday, the largest load of wood hauled into Brewer, was brought from Holden Center for William Burke’s Brick Yard. It was hauled by a pair of horses owned by George Hinman, of South Brewer, and measured three and a half cords. The Brewer Brick Cart originated here. It was a four wheeled cart with straight axles. The hind wheels were larger than the fore. The entire weight balanced on the hind wheels. The cart could be turned. The front was hooked down but when released, would let the cart body tip up in front, thus allowing the brick to run out.

It has been said that for a time the US Government used Brewer brick for a standard. At that time, all government orders were written “to be constructed of Brewer brick, or the equal.” These bricks were made from fine gray clay, and seemed to have an indefinite lifetime. A shipload of bricks was from 35,000 to 55,000. The rate on shipping bricks to North Carolina was cheaper than it was to Boston. The reason for this was that bricks were in demand for ballast on ships that carried hay to North Carolina. However, a great many of the bricks were shipped to Boston where they were sold at auction on the market by commission merchants.

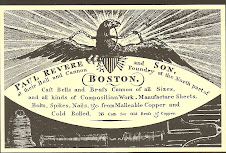

Brick making in Maine is said to have begun at almost the same time that settlement began. Apparently, there was brick made for shipment before the middle of the eighteenth century by some parts of the District of Maine. One reason for large shipments to Boston was that it required buildings of brick construction rather than the wood that had been used for its earliest structures. Many sections of the city were situated below grade and prone to continual dampness; wood structures would quickly rot whereas brick insured greater longevity for buildings hence greater profitability. The rebuilt section of Boston is said to have been constructed almost entirely of Brewer brick.

In 1867, about a dozen companies were making brick; one of the larger producers was the Brewer Steam Brick Company. There was a great demand for Brewer brick all over New England, but it was also being shipped to North Carolina, Florida, Texas, and the West Indies, and Newfoundland on a regular basis.

The building material in the Good Shepherd Convent in Van Buren, and in Bangor City Hall (the old one) had its origin here. The brick used in the old Bangor YMCA were hand pressed and made in Frank Graten’s Yard. Some old notes have been found that document Fort Sumter’s construction with Brewer brick. This is likely, given that large numbers of brick were shipped to this region during the time of the Fort’s construction.

In 1902, the year the middle span of the Bangor-Brewer Bridge was washed out; a Brewer brick yard had the contract to finish the brick for the Bangor Court House. At that time a temporary bridge was improvised so that travel between the two cities might not be cut off. Mr. Harrison Brooks and the Littlefield family have long been names that were connected with brick making in Brewer through their joint ownership of the Brooks Brick Company.

Now the brick making machinery is silent. The brick cart stands empty and disconsolate, and the sky above Brewer no longer glows with the flames from its long burning kilns.

Friday, April 24, 2009

Thursday, April 2, 2009

Author Wilbur Wolf at The Curran Homestead's 13th Annual Maple Syrup & Irish Celebration on Saturday, April 4, 10AM-2PM

At The Curran Homestead Living History Farm and Museum’s 13th Annual Maple Syrup and Irish Celebration, Saturday, April 4 , 10AM-2PM, , author Wilbur Wolf will be offering signed copies of his new book Memoirs of a Farmboy. Wolf will discuss and answer questions about the almost two hundred year history of his family’s farm highlighting his experiences growing up on the small dairy in Upstate New York during the 30s through the 50s. According to Dr. Robert Schmick, Volunteer Director of Education, “such experiences are becoming more unique with each passing day in America as small family farms are consumed by corporate owned agro-businesses and many more are simply re-purposed for residential subdivisions and strip malls,” so pick up a copy of this book, have it signed, and help support The Curran Homestead Living History Farm and Museum in its mission to preserve one Maine family farm and keep the experiences of Maine rural life alive for present and future generations.

Saturday, April 4, from 10AM-2PM, has been declared the date of the 13th Annual Curran Homestead Maple Festival & Irish Celebration Day by John Mugnai, President of the Living History Farm and Museum Board of Directors. The Curran Living History Farm and Museum on Fields Pond Road in Orrington will come to life with shared yarns spun about the good ole days around the wood burning stove. Meet Bodica and Mulls, the shaggy haired Scottish Highland cows and some lambs too. Enjoy an Easter egg hunt with the kids. Experience an ongoing demonstration of how to make maple syrup. Taste maple syrup, maple sugar baked beans, and corn chowder. Savor Cathy Martinage’s Irish stew (its main ingredient courtesy of Dan Hughes’ A Wee Bit Farm) and her Irish soda bread too. Sing along to the Irish folk music of Jerry Hughes. Also, meet Hugh Curran, an expert on Celtic culture, mythology, and spirituality. This event promises to be a step back in history to a simpler time of food, fun, and entertainment on the farm with the whole community invited. Event admission for members and donors is $5 per adult and $3 per child (under 12). For non-members, admission is $7 per adult and $5 per child (under 12), and this includes refreshments and participation in all events.

Saturday, April 4, from 10AM-2PM, has been declared the date of the 13th Annual Curran Homestead Maple Festival & Irish Celebration Day by John Mugnai, President of the Living History Farm and Museum Board of Directors. The Curran Living History Farm and Museum on Fields Pond Road in Orrington will come to life with shared yarns spun about the good ole days around the wood burning stove. Meet Bodica and Mulls, the shaggy haired Scottish Highland cows and some lambs too. Enjoy an Easter egg hunt with the kids. Experience an ongoing demonstration of how to make maple syrup. Taste maple syrup, maple sugar baked beans, and corn chowder. Savor Cathy Martinage’s Irish stew (its main ingredient courtesy of Dan Hughes’ A Wee Bit Farm) and her Irish soda bread too. Sing along to the Irish folk music of Jerry Hughes. Also, meet Hugh Curran, an expert on Celtic culture, mythology, and spirituality. This event promises to be a step back in history to a simpler time of food, fun, and entertainment on the farm with the whole community invited. Event admission for members and donors is $5 per adult and $3 per child (under 12). For non-members, admission is $7 per adult and $5 per child (under 12), and this includes refreshments and participation in all events.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)