As many who are local to the area know, one of the major defeats of the Continental Navy during the American Revolution occurred right on the Penobscot between Castine and Brewer. The story goes that Continental forces had planned to recapture Castine from the British. Some four hundred soldiers under the cover of fog attacked British fortifications at Castine resulting in their enemy’s hasty retreat.

The land assault was to be followed up by a naval attack under the command of Commodore Dudley Saltonstall of New Haven, CT, but the opportunity was missed when he “stubbornly refused to fight, opposed demanding surrender, and would not cooperate with the lands forces ” (Smith 234). The land forces gained ground threatening the British position while Saltonstall, with a naval force of nineteen armed vessels and twenty four vessels, most privately owned and piloted, remained at a safe distance and fired his cannons. After two weeks of holding this position, Sir George Collier with a force of seven ships maneuvered in range of Saltonstall and fired a broadside.

Avoiding any chance of loss or seizure of their private property, the interests of the privateers aiding the Continental Navy took precedence over any obligation they felt to the patriot cause; they retreated from Collier’s attack. The Continental Navy and Army's position immediately deteriorated resulting in an order to scuttle both vessels and transports, regardless of who owned them, in order to keep them out of the hands of the British. Some vessels were run aground, blown-up, or set afire while some fled up the Penobscot under pursuit.

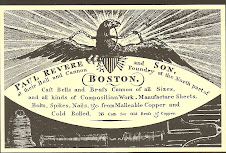

Land forces scattered and were forced to retreat through dense forest, and many soldiers subsequently died from hunger and exposure during their flight to safety. Some of the fleet made their way to a point between Brewer and Bangor where they were burned to the waterline and sunk. As a result of these losses, Saltonstall faced a court martial and was ordered to never hold a commission again while other participants in the failed land attack, including Paul Revere who commanded the ordinance, were honorably acquitted.

Two hundred plus years later our guest speaker Brent Phinney located the remains of one of Saltonstall’s fleet while scuba diving for the remains of the nine vessels of this fleet known to have gone down in the vicinity of Brewer and Bangor. The location of the surviving hull is about midway between the location of the Muddy Rudder Restaurant on the Brewer side and the harbor master’s office on the Bangor side of the river. The discovery resulted in the honor of having this site declared on later US Navy mapping as the “Phinney Site.”

Remarkably timbers, cannon balls, and other defining artifacts remained at the bottom of the river at a fortuitous position near the shore; it was fortuitous because this wreck had largely escaped the severe churning and abrasive nature of winter ice flows of the Penobscot for over two hundred years. This phenomena, Phinney theorizes, likely swept away the remains of the eight other Continental Navy vessels known to have been scuttled.

The wreck is in every sense of the word that, a wreck, for much of what remains is everything below the ship’s original waterline, and this lay largely buried under sediment. There are charred timbers visible that have undoubtedly survived decay because of that circumstance alone. A US Navy survey over the course of four consecutive summers by student divers recovered and photographed many artifacts at the site. Undoubtedly the BHS would be interested in obtaining some copies of those photographs for its own archives.

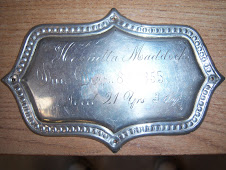

One of the greatest finds at the site occurred when Phinney himself accompanied the US Navy divers. As an expert on local ship building, be was aware that ship builders often placed a coin under a hollowed out spot on the mast deck before mounting the main mast of a ship. This was considered a talisman. The mast of this wreck had long since been destroyed or displaced but after removing sediments from its original position there lay the oxidized coin. It was later revealed after cleaning to be a 1708 Spanish silver coin. Phinney shared a photograph with the BHS that illustrated the remarkably good condition of the obverse and reverse of the coin. This find remains with all other objects recovered from the site under US Navy stewardship.

A testing of wood samples from the wreck confirmed that this particular vessel was constructed of trees from what is now the State of Maine. Maine, particularly Brewer and Bangor, were responsible for some 161 large wooden vessels during their tenure as premier ship building locations until 1919. In that year, which also marked the armistice of “the war to end all wars,” the building of large four mast sail boats ended with the launching of the last of its kind, the 1000 ton, 210 foot Horace Munroe. The occasion was marked by a dramatic mishap when the schooner slid down its rail faster than expected during the launch, and seamen missed their opportunity to drop anchor. The schooner raced across the Penobscot crashing into the McLaughlin & Company warehouse on the Bangor shore. It had to be towed back to Brewer and repaired.

From 1849-1919 there were four major shipyards producing barkentines, schooners, and other types of sailcraft on the Brewer shoreline. These shipyards changed hands a few times during this seventy year period, but Cooper and Dunning, McGilvery, which was later E. and I.K. Stetson, Gibbs and Phillips, Barbour, and Oakes were among the most prominent. The site of the McGilvery shipyard is currently Brent Phinney’s own steel shipbuilding enterprise. Unlike his antecedents he constructs boats using I-beams and metal plating as well as using modern hydraulics for dry-docking and launching the boats in his yard. His projects are usually limited to 65 feet in length weighing anywhere between 90 and 300 tons.

In days of yore elaborate wooden scaffolding was part of the formula for creating and launching wooden vessels. A wooden rail was lubricated with bear’s grease to insure a smooth glide down to the river’s surface. Oxen and horses were employed in these constructions as well. Seventy five men usually took a year to a year and a half to transform the hand shaped wooden timbers and wrought iron spikes and hardware into a seaworthy vessel. There was no better place for making wooden ships, for Maine is blessed with one of the greatest wood supplies that the world has ever known. Local sapwoods like hacmatack and hardwoods like oak were especially important to boat construction. Local brickyards also supplied brick ballast for these ships.

Phinney has put together a small museum gallery at his office on the Brewer shoreline; here are framed pictures of the Horace Munroe and Charles D. Sanford, which was launched in 1918, among many others. The latter ship also encountered difficulties at its launching sticking fast to the rail during its send off, and the launch was postponed for another day. In 1874, the Claire McGilvery must have displaced much water weighing in at 1329 tons at the McGilvery shipyard. William McGilvery had begun shipbuilding in Searsport, but by 1867 the barkantine Manson was launched from his Brewer site marking decades more of successful ship production.

In addition to photos, Phinney shared some of the tools of the trade of shipbuilding, including an adze, an early rotary measure, and a right-handed axe that had come down through his family by way of a great uncle in Steuben who had been a shipwright. During Phinney’s restoration of the shoreline of his property and while digging footings for a new building on the site, he has uncovered layers of shipbuilding activity below the surface. Among dense wood shavings and sawdust, these layers have produced numerous wrought iron spikes and wood staples once used for joining wood ship timbers. There are also numerous metal files which Phinney reckons were used for sharpening all the hand tools used daily during ship construction.

Phinney also brought with him a wood knee that would have been familiar and numerous in a shipyard in the past but would likely puzzle some of us today on what its purpose had once been. Used for supporting decking as well as for reinforcing corners, these hand carved components were made from hacmatack. According to Henry Wiswell, President of the Orrington Historical Society and attendee, local farmers would produce such components themselves and sell them to local shipyards for extra money; he has family records that rate the cost of a ship knee at a dollar apiece in the first half of the 19th century.

Such artifacts inspired much thought about the shear manpower, magnitude, and ingenious methods employed on these solely wooden constructions as Phinney's antique shipwright's tools and vintage photos were passed around the room by BHS members and the general public in attendance this past Tuesday, March 3 evening. We are fortunate that we have Brent Phinney to collect what information and material culture he can from this important chapter not only in Brewer history but the nation’s own, and share it with us in person and through its preservation as a recording in our ever-evolving oral history archive.

References

Smith, Marion Jaques. A History of Maine; From Wilderness To Statehood. Portland, ME: Falmouth Publishing House, 1949.

Friday, March 13, 2009

Wednesday, March 11, 2009

An Opinion Regarding The Tefft House Project

There are two primary reasons to have a house for the BHS: 1) the physical space provides a place to meet, educate members of the BHS, and plan, and 2) larger crowds of people not directly affiliated with the BHS are allowed to learn about history important to the BHS and hopefully in the future they become involved in preserving important parts of our past.

The Tefft house has a lot of desirable elements that any good-willed historic society would want: provenance, location and parking, generous sized rooms, and plenty of room to rent out in order to supplement overhead. Everyone knows the house would require hundreds of thousands of dollars to repair. Even more if the decision was made to restore it. Most of the work is structural, making work contribution from the members not plausible. Once it gets to the decorating stage, most folks would probably love to get involved.

After completion the house would be an enormous asset to the BHS and the community. People would want to photograph it for magazines. People would want tours. I think you have a wonderful small house now. That is an asset. You also have a great curator who tells me he can obtain grants. That is an asset.

If the intention of this building is to take on a museum quality, then I like the idea of making it a regional museum, something like the Penobscot Museum, and working with all the towns in the area. Ask people for donations of objects for display, objects that can be sold to raise money, donations of money, stocks, building materials, or just their time. Make it kid friendly so parents will want to take their kids there after school.

If you can get the building and sell the current house, one room can be taken at a time. Certainly it won't need the expensive work of a kitchen. Maybe a decorator with a computer program could generate some representations of how some rooms would look after completion to stir up interest and involvement. The downside of the project is well known to everyone: enormous cost, current state of the economy, funding must be ongoing with someone attending to that constantly. I believe the previous owners bought the property always intending to fix up the house, yet never had the membership, the community involvement, or the ability or know-how to tap into local, state or federal funds. You have some of the same problems but you may have some people better equipped at finding money.

Dan Moellentin, PharmD

Clinical Specialist-Pharmacotherapy

207-973-6968 (office)207-851-4106 (text pager)

The Tefft house has a lot of desirable elements that any good-willed historic society would want: provenance, location and parking, generous sized rooms, and plenty of room to rent out in order to supplement overhead. Everyone knows the house would require hundreds of thousands of dollars to repair. Even more if the decision was made to restore it. Most of the work is structural, making work contribution from the members not plausible. Once it gets to the decorating stage, most folks would probably love to get involved.

After completion the house would be an enormous asset to the BHS and the community. People would want to photograph it for magazines. People would want tours. I think you have a wonderful small house now. That is an asset. You also have a great curator who tells me he can obtain grants. That is an asset.

If the intention of this building is to take on a museum quality, then I like the idea of making it a regional museum, something like the Penobscot Museum, and working with all the towns in the area. Ask people for donations of objects for display, objects that can be sold to raise money, donations of money, stocks, building materials, or just their time. Make it kid friendly so parents will want to take their kids there after school.

If you can get the building and sell the current house, one room can be taken at a time. Certainly it won't need the expensive work of a kitchen. Maybe a decorator with a computer program could generate some representations of how some rooms would look after completion to stir up interest and involvement. The downside of the project is well known to everyone: enormous cost, current state of the economy, funding must be ongoing with someone attending to that constantly. I believe the previous owners bought the property always intending to fix up the house, yet never had the membership, the community involvement, or the ability or know-how to tap into local, state or federal funds. You have some of the same problems but you may have some people better equipped at finding money.

Dan Moellentin, PharmD

Clinical Specialist-Pharmacotherapy

207-973-6968 (office)207-851-4106 (text pager)

Tuesday, March 10, 2009

One Opinion Regarding the Tefft House

In regard to how BHS might secure the future of the Tefft House a consortium of participants who purchase, restore, maintain, and use the building for nonprofit activity is an idea worth further discussion. I think that the Brewer Historical Society ultimately wants the building preserved, but the issue of restoration and maintenance of this amount of square footage is an obstacle at this point. In embracing some of the terminology that has been bandied about in the media and political circles, "transparency" might be a key to moving forward on this project. That would be transparency with others outside the BHS circle, or "box" (you choose the metaphor).

Why not announce in the papers BHS's intentions, set a date, have a forum with local non-profits who can see themselves in the building and making use of it, if it were brought back from the dead and infused with life again? Such a meeting might be productive. We, the BHS, could sell the community on the idea with a power point presentation with some mock-up art work, computer generated or other, of what the building could be. I volunteer to create a presentation package with a mock up of what the house could look like ( I would need some help), using materials had at the local art supply store. This would explore an alternative to the BHS buying the building solo and create a shared ownership situation. Its proposed use as a museum, use as an arts, folklore, and cultural center, would not change but it could also be a number of other things too. There is the potential for a large archival and artifact storage etc. of not only the BHS’s holdings but other local historical societies who have a mission to collect and preserve but currently don’t have a facility of their own. A combined collection of all these institutions would offer “one stop shopping” for the public through greater access for perusal and research as well as display.

An idea might be to sell the idea to Eddington Historical Society, Orrington Historical Society, as well as Brewer Historical Society as a project that all could benefit from, and that all could potentially profit from with greater opportunity for grant funding, public admission revenues, and reproduction sales especially of document facsimiles and vintage photo scans. Overtures might also be made to other nonprofits. You tell me who they might be? Combining forces and creating something together for the first time---A museum that serves all three areas---"as one we are many") Each communities' identity could be served and preserved (emphasizing that to these institutions would be key) through a board with representatives from each. Each historical society could continue to exist and nurture their current constituencies, but there would be a greater opportunity to attract whole new age and interest demographics if there was having a museum at the heart of their respective missions.

After all these communities all share a common high school, why not a common museum? A Board made up of all these would be key. Each historical society could seek grant money on their own as well. . These organizations all need a place for their stuff, and insuring such a place would be more likely with a shared opportunity like this. All these organizations would be interested in their own survival, and creating such a facility would better insure that and the realization of why artifacts and documents are preserved---for people to see and learn from. A place like this could serve to generate funds to keep them all thriving. Federal and state grant organizations would be highly receptive to a partnership rather than a single, small institution seeking funding.

Pooled resources, both financial and in-kind services, for such a project would ultimately result in a significant museum that might be comparable one day to museums found in Bangor or even Portland someday. Keeping up with the Jones’ is exactly what a global market economy is all about, and cultural/history institutions have to take on the responsibility of being competitive if they plan on surviving for up and coming generations, and it is necessary in this point in time to see the nonprofit as a business just like any that is for profit. I am not seeing 20, 30, and 40 year olds filling the chairs at these local historical societies. How can that happen? Something like this that offers something to them might be the way to get these groups interested in preserving local history and developing a cultural institution for their community.

Beyond local residents, such a place could draw people from outside the community for its records, archives, material culture, and art like three small historical societies have never done and will never do unless they happen on some presently unforeseen gimmick. Creating a place that preserves the present missions of these institutions while at the same time broadening their scope to serve new audiences that aren't (seemingly) served by the old historical society model seems a “no brainer” in regard to insuring their future survival and growth. In addition, there are other organizations that could continue to fulfill their mission and preserve their identity while at the same time joining forces in the "Penobscot Area Center for History, Culture, and Folklore," or some other such name that would embrace all of these organizations as one multi-tiered entity housed within the Tefft House.

I think the real sell for this type of concept is that partnerships always fly well with state and federal funding. A museum in the community would inspire other services and growth. It would inspire more people to the Brewer downtown, and maybe some of those numerous “buildings for sale” and “for lease or rent” maybe attractive to people that see a museum in the community as a sign of real growth and development. This type of concept would also create real paying jobs and real income in such building as well because there are endless ways to sell history, culture, and art. Having groups, school children, and tourists coming to check out this museum would resonate throughout the community. If you are in doubt check about how a museum contributes to the perception and optimism of a community check out the Maine Maritime Museum during the summer months or even the Maine Discovery Museum. A museum in Brewer would benefit many other businesses.

I loved Brent Finney’s lecture, and there will be something about that on the blog soon. I was thinking when Mr. Finney shared the story of Commodore Dudley Saltonstall’s scuttled fleet that one potential money maker might be scuba expeditions to that Revolutionary War wreck found between Brewer and Bangor in the Penobscot. Forget about raising the stuff from the Penobscot, why not protect the sight and have people see it in situ .I can’t believe that some rusted cannon balls, rotten timbers, and the like will generate all that much interest in some building, but seeing it underwater would have an appeal to scuba enthusiasts. The BHS could sponsor such a summer program and share monies taken in with the experienced diver leaders and boat pilots you would need to lead such expeditions. Something to bandy about with the gang. Success stories start with dreams.

Robert Schmick, Ph.D

email: rpschmick1@aol.com

Why not announce in the papers BHS's intentions, set a date, have a forum with local non-profits who can see themselves in the building and making use of it, if it were brought back from the dead and infused with life again? Such a meeting might be productive. We, the BHS, could sell the community on the idea with a power point presentation with some mock-up art work, computer generated or other, of what the building could be. I volunteer to create a presentation package with a mock up of what the house could look like ( I would need some help), using materials had at the local art supply store. This would explore an alternative to the BHS buying the building solo and create a shared ownership situation. Its proposed use as a museum, use as an arts, folklore, and cultural center, would not change but it could also be a number of other things too. There is the potential for a large archival and artifact storage etc. of not only the BHS’s holdings but other local historical societies who have a mission to collect and preserve but currently don’t have a facility of their own. A combined collection of all these institutions would offer “one stop shopping” for the public through greater access for perusal and research as well as display.

An idea might be to sell the idea to Eddington Historical Society, Orrington Historical Society, as well as Brewer Historical Society as a project that all could benefit from, and that all could potentially profit from with greater opportunity for grant funding, public admission revenues, and reproduction sales especially of document facsimiles and vintage photo scans. Overtures might also be made to other nonprofits. You tell me who they might be? Combining forces and creating something together for the first time---A museum that serves all three areas---"as one we are many") Each communities' identity could be served and preserved (emphasizing that to these institutions would be key) through a board with representatives from each. Each historical society could continue to exist and nurture their current constituencies, but there would be a greater opportunity to attract whole new age and interest demographics if there was having a museum at the heart of their respective missions.

After all these communities all share a common high school, why not a common museum? A Board made up of all these would be key. Each historical society could seek grant money on their own as well. . These organizations all need a place for their stuff, and insuring such a place would be more likely with a shared opportunity like this. All these organizations would be interested in their own survival, and creating such a facility would better insure that and the realization of why artifacts and documents are preserved---for people to see and learn from. A place like this could serve to generate funds to keep them all thriving. Federal and state grant organizations would be highly receptive to a partnership rather than a single, small institution seeking funding.

Pooled resources, both financial and in-kind services, for such a project would ultimately result in a significant museum that might be comparable one day to museums found in Bangor or even Portland someday. Keeping up with the Jones’ is exactly what a global market economy is all about, and cultural/history institutions have to take on the responsibility of being competitive if they plan on surviving for up and coming generations, and it is necessary in this point in time to see the nonprofit as a business just like any that is for profit. I am not seeing 20, 30, and 40 year olds filling the chairs at these local historical societies. How can that happen? Something like this that offers something to them might be the way to get these groups interested in preserving local history and developing a cultural institution for their community.

Beyond local residents, such a place could draw people from outside the community for its records, archives, material culture, and art like three small historical societies have never done and will never do unless they happen on some presently unforeseen gimmick. Creating a place that preserves the present missions of these institutions while at the same time broadening their scope to serve new audiences that aren't (seemingly) served by the old historical society model seems a “no brainer” in regard to insuring their future survival and growth. In addition, there are other organizations that could continue to fulfill their mission and preserve their identity while at the same time joining forces in the "Penobscot Area Center for History, Culture, and Folklore," or some other such name that would embrace all of these organizations as one multi-tiered entity housed within the Tefft House.

I think the real sell for this type of concept is that partnerships always fly well with state and federal funding. A museum in the community would inspire other services and growth. It would inspire more people to the Brewer downtown, and maybe some of those numerous “buildings for sale” and “for lease or rent” maybe attractive to people that see a museum in the community as a sign of real growth and development. This type of concept would also create real paying jobs and real income in such building as well because there are endless ways to sell history, culture, and art. Having groups, school children, and tourists coming to check out this museum would resonate throughout the community. If you are in doubt check about how a museum contributes to the perception and optimism of a community check out the Maine Maritime Museum during the summer months or even the Maine Discovery Museum. A museum in Brewer would benefit many other businesses.

I loved Brent Finney’s lecture, and there will be something about that on the blog soon. I was thinking when Mr. Finney shared the story of Commodore Dudley Saltonstall’s scuttled fleet that one potential money maker might be scuba expeditions to that Revolutionary War wreck found between Brewer and Bangor in the Penobscot. Forget about raising the stuff from the Penobscot, why not protect the sight and have people see it in situ .I can’t believe that some rusted cannon balls, rotten timbers, and the like will generate all that much interest in some building, but seeing it underwater would have an appeal to scuba enthusiasts. The BHS could sponsor such a summer program and share monies taken in with the experienced diver leaders and boat pilots you would need to lead such expeditions. Something to bandy about with the gang. Success stories start with dreams.

Robert Schmick, Ph.D

email: rpschmick1@aol.com

Sunday, March 1, 2009

Board Considers Purchase of Historic Property

The Tefft family home at 235 Center Street, Brewer, was for many years the headquarters of the Veterans of Foreign Wars Post No. 4917, but it is now for sale. The Brewer VFW post will be merging with the Bangor VFW. The house has been a meeting place for, not only veterans, but organizations like Alcoholics Anonymous, the local Boy Scout Troop, and others as well as bingo games, dances, receptions, and events for decades. It was built in 1837 as a private residence by Dr. Horatio N. Page and later purchased by the parents of brothers Charles Eugene Tefft, a nationally recognized sculptor, and Nathan Tefft, a playwright and author, who grew up there.

At the January Board of Directors meeting, it was decided to pursue the possibility of the Brewer Historical Society purchasing the building. President Jeffrey Hamadey announced to members at the February 3rd meeting at the Brewer Auditorium that a subcommittee of members were researching the feasibility of selling the Clewley House on Wilson Street, Brewer, and moving the museum to this Center Street mansion location.

Board members have done a number of walk throughs of the property. Most recently, this past Friday, February 27, members did a close inspection of this Federal style house. The property consists of two parts: the original three-story brick structure and a one story cinder, or cement, block addition, which one VFW Post member in attendance reported was constructed in "1966." This meeting hall addition consists of a floor space roughly a thousand square plus feet in size. It has an adjacent room in the house structure where the kitchen with its stainless steel sink and counter as well as a commercial gas stove is located. The basement that runs below the hall has been used for Boy Scout meetings until recently; it is accessed by an interior staircase.

From the meeting hall, one can gain entry to the central staircase of the historic house. The photos included here on the blog attest to its magnificence even after more than a century and a half of use and disuse. The lines and curves of the interior evidence the work of master craftsmen. The central staircase's natural wood finish hand rail subtly bends at the middle and reaches to the second floor landing contrasting with the numerous painted spindle balusters. This produces a symmetrical perfection noticed by all who enter the original front hallway. Within sight of the stairs on the second floor is another and narrower set of stairs which leads to the third floor (see photo detail). This also has some beautiful lines expressed in its plaster and lathe underside and the curve of its wood rail. The third floor had been an apartment recalled one veteran onsite but it has more recently served as a storage space.

The floors throughout the house ( see photo detail) are of a rough plank type evidencing that these were originally meant to be completely covered rather than made visible amidst the contrasting opulence of the original quality doors, windows, fireplaces, staircase and wall and cieling plastering extant. It was pointed out by someone that some of the early floor covering, or at least the underlayer of it, could presently be found in situ at the bottom of the main stairs.

The second floor has some very spacious rooms, and the original moldings of these are seemingly intact. Details include a four-petal floral blossom design in each corner of the door lintels (see photo detail). The wooden trim moldings of each door are deeply fluted. Windows are also seemingly original measuring some 30 plus inches in width with 6 over 6 panes of glass. The intact window treatments include 4 over 4 folding shutters with single panel centers. These do not fold into pocket recesses as is often seen in Victorian era homes, but rather are hinged to the wood trim frame of each interior window. They are left visible when folded back.

The painted fireplace moldings are of simple design with an unornamented plinth block at each side and a vertical shaft of two fluted strips. The horizontal frieze consists of two raised and rounded strips that complement the fluting of the vertical shafts. There is a backsplash to the top mantel surface itself which is of a narrow and unornamented board. There is the remains of a cast iron firebox insert in one of the fireplaces on the second floor.

The large second floor front room appears to have been two rooms originally, for there are visible signs of a dividing wall that once existed. It is obvious from this room layout that there were never any more than four functioning windows on the side of the house facing Center Street. The bricked-in window recesses visible on the exterior are not evidence of an afterthought and subsequent alteration but were simply a means of achieving symmetry in the original design of eight window recesses with four functioning windows on the houses left side. From the early glass plate photo of the house included here, it seems that the house was situated to face the Penobscot River. It is conceivable that no other houses existed before it to prohibit a full view of the river and passing ships from the front porch in early antebellum Brewer.

It occurred to me while walking through the house this past Friday of how fortunate I was to see this early local structure that has undergone relatively little alteration since its heyday. The "modern" alterations that characterize so many existing houses from the antebellum era across America today have surprisingly been avoided in this structure because of the existence of the addition of the meeting hall in the 1960s and the subsequent subordinate use of the main structure by the VFW Post. Much of the plaster and lathe of its interior spaces has avoided damage, although water damage has taken its toll on some of the interior. Windows have never been updated to deter heat loss. Cielings have not been enclosed by drop cielings to preserve heat. Wooden moldings have largely avoided damage usually sustained with electrical and heating updates and the like. These are good things in the eyes of the preservationist.

Whether or not BHS decides in favor of the purchase, a commitment by a group or individuals to the rejuvenation of such an architectural treasure as this from Brewer's past will contribute considerably to the public's perception of this city's promise and potentialities for not only the future but the here and now. Such a preservation project would rekindle the power it and other like structures once had to ornament and highlight the valuable human resources of our community as well as serve as a continued and uninterrupted meeting and learning place for them.

At the January Board of Directors meeting, it was decided to pursue the possibility of the Brewer Historical Society purchasing the building. President Jeffrey Hamadey announced to members at the February 3rd meeting at the Brewer Auditorium that a subcommittee of members were researching the feasibility of selling the Clewley House on Wilson Street, Brewer, and moving the museum to this Center Street mansion location.

Board members have done a number of walk throughs of the property. Most recently, this past Friday, February 27, members did a close inspection of this Federal style house. The property consists of two parts: the original three-story brick structure and a one story cinder, or cement, block addition, which one VFW Post member in attendance reported was constructed in "1966." This meeting hall addition consists of a floor space roughly a thousand square plus feet in size. It has an adjacent room in the house structure where the kitchen with its stainless steel sink and counter as well as a commercial gas stove is located. The basement that runs below the hall has been used for Boy Scout meetings until recently; it is accessed by an interior staircase.

From the meeting hall, one can gain entry to the central staircase of the historic house. The photos included here on the blog attest to its magnificence even after more than a century and a half of use and disuse. The lines and curves of the interior evidence the work of master craftsmen. The central staircase's natural wood finish hand rail subtly bends at the middle and reaches to the second floor landing contrasting with the numerous painted spindle balusters. This produces a symmetrical perfection noticed by all who enter the original front hallway. Within sight of the stairs on the second floor is another and narrower set of stairs which leads to the third floor (see photo detail). This also has some beautiful lines expressed in its plaster and lathe underside and the curve of its wood rail. The third floor had been an apartment recalled one veteran onsite but it has more recently served as a storage space.

The floors throughout the house ( see photo detail) are of a rough plank type evidencing that these were originally meant to be completely covered rather than made visible amidst the contrasting opulence of the original quality doors, windows, fireplaces, staircase and wall and cieling plastering extant. It was pointed out by someone that some of the early floor covering, or at least the underlayer of it, could presently be found in situ at the bottom of the main stairs.

The second floor has some very spacious rooms, and the original moldings of these are seemingly intact. Details include a four-petal floral blossom design in each corner of the door lintels (see photo detail). The wooden trim moldings of each door are deeply fluted. Windows are also seemingly original measuring some 30 plus inches in width with 6 over 6 panes of glass. The intact window treatments include 4 over 4 folding shutters with single panel centers. These do not fold into pocket recesses as is often seen in Victorian era homes, but rather are hinged to the wood trim frame of each interior window. They are left visible when folded back.

The painted fireplace moldings are of simple design with an unornamented plinth block at each side and a vertical shaft of two fluted strips. The horizontal frieze consists of two raised and rounded strips that complement the fluting of the vertical shafts. There is a backsplash to the top mantel surface itself which is of a narrow and unornamented board. There is the remains of a cast iron firebox insert in one of the fireplaces on the second floor.

The large second floor front room appears to have been two rooms originally, for there are visible signs of a dividing wall that once existed. It is obvious from this room layout that there were never any more than four functioning windows on the side of the house facing Center Street. The bricked-in window recesses visible on the exterior are not evidence of an afterthought and subsequent alteration but were simply a means of achieving symmetry in the original design of eight window recesses with four functioning windows on the houses left side. From the early glass plate photo of the house included here, it seems that the house was situated to face the Penobscot River. It is conceivable that no other houses existed before it to prohibit a full view of the river and passing ships from the front porch in early antebellum Brewer.

It occurred to me while walking through the house this past Friday of how fortunate I was to see this early local structure that has undergone relatively little alteration since its heyday. The "modern" alterations that characterize so many existing houses from the antebellum era across America today have surprisingly been avoided in this structure because of the existence of the addition of the meeting hall in the 1960s and the subsequent subordinate use of the main structure by the VFW Post. Much of the plaster and lathe of its interior spaces has avoided damage, although water damage has taken its toll on some of the interior. Windows have never been updated to deter heat loss. Cielings have not been enclosed by drop cielings to preserve heat. Wooden moldings have largely avoided damage usually sustained with electrical and heating updates and the like. These are good things in the eyes of the preservationist.

Whether or not BHS decides in favor of the purchase, a commitment by a group or individuals to the rejuvenation of such an architectural treasure as this from Brewer's past will contribute considerably to the public's perception of this city's promise and potentialities for not only the future but the here and now. Such a preservation project would rekindle the power it and other like structures once had to ornament and highlight the valuable human resources of our community as well as serve as a continued and uninterrupted meeting and learning place for them.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)