As many who are local to the area know, one of the major defeats of the Continental Navy during the American Revolution occurred right on the Penobscot between Castine and Brewer. The story goes that Continental forces had planned to recapture Castine from the British. Some four hundred soldiers under the cover of fog attacked British fortifications at Castine resulting in their enemy’s hasty retreat.

The land assault was to be followed up by a naval attack under the command of Commodore Dudley Saltonstall of New Haven, CT, but the opportunity was missed when he “stubbornly refused to fight, opposed demanding surrender, and would not cooperate with the lands forces ” (Smith 234). The land forces gained ground threatening the British position while Saltonstall, with a naval force of nineteen armed vessels and twenty four vessels, most privately owned and piloted, remained at a safe distance and fired his cannons. After two weeks of holding this position, Sir George Collier with a force of seven ships maneuvered in range of Saltonstall and fired a broadside.

Avoiding any chance of loss or seizure of their private property, the interests of the privateers aiding the Continental Navy took precedence over any obligation they felt to the patriot cause; they retreated from Collier’s attack. The Continental Navy and Army's position immediately deteriorated resulting in an order to scuttle both vessels and transports, regardless of who owned them, in order to keep them out of the hands of the British. Some vessels were run aground, blown-up, or set afire while some fled up the Penobscot under pursuit.

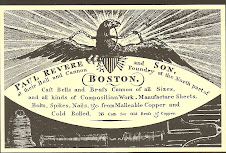

Land forces scattered and were forced to retreat through dense forest, and many soldiers subsequently died from hunger and exposure during their flight to safety. Some of the fleet made their way to a point between Brewer and Bangor where they were burned to the waterline and sunk. As a result of these losses, Saltonstall faced a court martial and was ordered to never hold a commission again while other participants in the failed land attack, including Paul Revere who commanded the ordinance, were honorably acquitted.

Two hundred plus years later our guest speaker Brent Phinney located the remains of one of Saltonstall’s fleet while scuba diving for the remains of the nine vessels of this fleet known to have gone down in the vicinity of Brewer and Bangor. The location of the surviving hull is about midway between the location of the Muddy Rudder Restaurant on the Brewer side and the harbor master’s office on the Bangor side of the river. The discovery resulted in the honor of having this site declared on later US Navy mapping as the “Phinney Site.”

Remarkably timbers, cannon balls, and other defining artifacts remained at the bottom of the river at a fortuitous position near the shore; it was fortuitous because this wreck had largely escaped the severe churning and abrasive nature of winter ice flows of the Penobscot for over two hundred years. This phenomena, Phinney theorizes, likely swept away the remains of the eight other Continental Navy vessels known to have been scuttled.

The wreck is in every sense of the word that, a wreck, for much of what remains is everything below the ship’s original waterline, and this lay largely buried under sediment. There are charred timbers visible that have undoubtedly survived decay because of that circumstance alone. A US Navy survey over the course of four consecutive summers by student divers recovered and photographed many artifacts at the site. Undoubtedly the BHS would be interested in obtaining some copies of those photographs for its own archives.

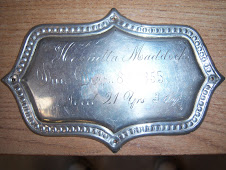

One of the greatest finds at the site occurred when Phinney himself accompanied the US Navy divers. As an expert on local ship building, be was aware that ship builders often placed a coin under a hollowed out spot on the mast deck before mounting the main mast of a ship. This was considered a talisman. The mast of this wreck had long since been destroyed or displaced but after removing sediments from its original position there lay the oxidized coin. It was later revealed after cleaning to be a 1708 Spanish silver coin. Phinney shared a photograph with the BHS that illustrated the remarkably good condition of the obverse and reverse of the coin. This find remains with all other objects recovered from the site under US Navy stewardship.

A testing of wood samples from the wreck confirmed that this particular vessel was constructed of trees from what is now the State of Maine. Maine, particularly Brewer and Bangor, were responsible for some 161 large wooden vessels during their tenure as premier ship building locations until 1919. In that year, which also marked the armistice of “the war to end all wars,” the building of large four mast sail boats ended with the launching of the last of its kind, the 1000 ton, 210 foot Horace Munroe. The occasion was marked by a dramatic mishap when the schooner slid down its rail faster than expected during the launch, and seamen missed their opportunity to drop anchor. The schooner raced across the Penobscot crashing into the McLaughlin & Company warehouse on the Bangor shore. It had to be towed back to Brewer and repaired.

From 1849-1919 there were four major shipyards producing barkentines, schooners, and other types of sailcraft on the Brewer shoreline. These shipyards changed hands a few times during this seventy year period, but Cooper and Dunning, McGilvery, which was later E. and I.K. Stetson, Gibbs and Phillips, Barbour, and Oakes were among the most prominent. The site of the McGilvery shipyard is currently Brent Phinney’s own steel shipbuilding enterprise. Unlike his antecedents he constructs boats using I-beams and metal plating as well as using modern hydraulics for dry-docking and launching the boats in his yard. His projects are usually limited to 65 feet in length weighing anywhere between 90 and 300 tons.

In days of yore elaborate wooden scaffolding was part of the formula for creating and launching wooden vessels. A wooden rail was lubricated with bear’s grease to insure a smooth glide down to the river’s surface. Oxen and horses were employed in these constructions as well. Seventy five men usually took a year to a year and a half to transform the hand shaped wooden timbers and wrought iron spikes and hardware into a seaworthy vessel. There was no better place for making wooden ships, for Maine is blessed with one of the greatest wood supplies that the world has ever known. Local sapwoods like hacmatack and hardwoods like oak were especially important to boat construction. Local brickyards also supplied brick ballast for these ships.

Phinney has put together a small museum gallery at his office on the Brewer shoreline; here are framed pictures of the Horace Munroe and Charles D. Sanford, which was launched in 1918, among many others. The latter ship also encountered difficulties at its launching sticking fast to the rail during its send off, and the launch was postponed for another day. In 1874, the Claire McGilvery must have displaced much water weighing in at 1329 tons at the McGilvery shipyard. William McGilvery had begun shipbuilding in Searsport, but by 1867 the barkantine Manson was launched from his Brewer site marking decades more of successful ship production.

In addition to photos, Phinney shared some of the tools of the trade of shipbuilding, including an adze, an early rotary measure, and a right-handed axe that had come down through his family by way of a great uncle in Steuben who had been a shipwright. During Phinney’s restoration of the shoreline of his property and while digging footings for a new building on the site, he has uncovered layers of shipbuilding activity below the surface. Among dense wood shavings and sawdust, these layers have produced numerous wrought iron spikes and wood staples once used for joining wood ship timbers. There are also numerous metal files which Phinney reckons were used for sharpening all the hand tools used daily during ship construction.

Phinney also brought with him a wood knee that would have been familiar and numerous in a shipyard in the past but would likely puzzle some of us today on what its purpose had once been. Used for supporting decking as well as for reinforcing corners, these hand carved components were made from hacmatack. According to Henry Wiswell, President of the Orrington Historical Society and attendee, local farmers would produce such components themselves and sell them to local shipyards for extra money; he has family records that rate the cost of a ship knee at a dollar apiece in the first half of the 19th century.

Such artifacts inspired much thought about the shear manpower, magnitude, and ingenious methods employed on these solely wooden constructions as Phinney's antique shipwright's tools and vintage photos were passed around the room by BHS members and the general public in attendance this past Tuesday, March 3 evening. We are fortunate that we have Brent Phinney to collect what information and material culture he can from this important chapter not only in Brewer history but the nation’s own, and share it with us in person and through its preservation as a recording in our ever-evolving oral history archive.

References

Smith, Marion Jaques. A History of Maine; From Wilderness To Statehood. Portland, ME: Falmouth Publishing House, 1949.

Subscribe to:

Post Comments (Atom)

No comments:

Post a Comment