Captain James Weeks, Professor Emeritus at Maine Maritime Academy, used a surgeon's skill to cut through the events that engulfed the passengers of the ill-fated ship Titantic on April 15th of 1912. Utilizing models that he had created, schematics and disgrams, Captain Weeks showed in detail how the luxury liner hit the iceberg that was to her doom and how the North Sea engulfed the ship until finally, in the early morning of the 15th, she slipped below the waves with a loss of life of over 1500 people. He explained how the lifeboats were half empty and how the ship, Carpathia, heroically led the rescue of those who survived.

There are some passenger ties to Maine. Jack Thayer, a teenager on board, was ultimately proved to be correct in his assertion that the ship broke in two despite the insistence by a ship's officer that it hadn't. Jack Thayer's granddaughter presently lives in Maine. In addition there was a member of the audience whose grandmother was a survivor. He recounted how the half-empty lifeboat would not return for floundering passengers either because the officer was afraid that the sinking ship would pull her under or because the scrambling of the boarding passengers might capsize her.

Captain Weeks said that there were two Titantics---the real Titantic and the Hollywood Titantic. No matter which Titantic you follow, there is the adventure and heroism and sacrifice of over 2200 human beings on that night to remember.

Sunday, November 15, 2009

Marketing the Historical Society in a New Era, by Robert Schmick

Having visited more than my fair share of museums, historical societies, and historic houses, I have become aware of some of the challenges that especially smaller institutions face in the wake of ever increasing competition for the time of their potential audiences. Not only has television, mass media, and electronic media changed the publics’ recreational activities, but for-profit corporations have taken on an increasing role in developing exhibitions, cultural programming, and edutainment in more densely populated areas that continue to overshadow and threaten especially small institutions with small budgets. This competition has made it necessary for small cultural institutions like the local historical society to focus directly on marketing strategies. Marketing, with its traditions of competition, has often been seen by the museum community as something for them to resist, but, such strategies can make an institution greater at serving a larger portion of their community.

Successful marketing strategies are founded on an understanding of the public and their needs, or perceived needs. Small institutions, like the local historical society, need to step up to the plate and deliver new and attractive ways of presenting themselves. They must drive the point home that they are the real thing, a place where meaningful objects and trustworthy information can be found and serve a role in their lives and their community. In doing this they negate all the fears about taking on the agenda of marketing. They also need to embrace history of more than the elite of the past, present other periods in history than merely the distant past, and, finally, take on the untraditional role of documenting and presenting their community’s more recent past through the mediums of our own time---digital photography and audio in order to more effectively disseminate the information they have, namely much of their collections that are in storage for long periods of time, and become more relevant to generations that have embraced new digital media.

Taking on the point of view of visitors, or potential visitors, may mean that the local historical society must transcend merely the historical narratives of the 17th-19th centuries and seek to satisfy the current demand for twentieth century nostalgia by baby boomers, Gen-Xers, and the like. This could be a strategy that will result in drawing more people into the institution’s fold for further growth and initiate some needed enthusiasm among greater numbers for the historical society’s existing collections.

In saying this, I am reminded of institutions in which very dedicated individuals scratch their heads and wonder why they have so few younger and middle aged among their membership. Of course, this is a demographic that is busy raising families and working, but they do have leisure time, and the question the historical societies should be asking is how do we make our institution relevant to this group and make them want to spend that leisure as a visitor to our facility or involved in the collecting of local history and its dissemination through education.

What might be some of the specific marketing strategies that would make these historical societies more relevant to the lives of more? The Andover Historical Society (AHS) in Andover, Massachusetts has sought to reinvent how their community members come to know about what they offer. Not long ago they struck upon the idea of organizing a farmers’ market where one no longer existed. Small farms have sprung up in increasing numbers in the past few decades in this suburban community not far from Boston. A local high school student actually sparked the idea when she contacted AHS and asked whether there were any markets in the area to sell garden produce. AHS sent out feelers about the possibility of them creating a market on the small village lot that they own, and many local farmers were ecstatic about the idea.

The Historical Society provided rental space for these local farmers right next to the historical house they maintain. This situation has allowed for this institution to participate in the making of local history rather than merely preserving the long-ago past. This scheme not only resulted in added revenues but renewed interest in the historical society. As people came out to buy produce, they seized the opportunity to walk the grounds, ask questions about the historic house, and visit it. The historical society used the opportunity of having the public on their grounds on a regular basis for the purpose of buying produce to provide outdoor programming and events more frequently. There was significant free press coverage through this arrangement as well.

Through this scheme this historical society has attracted a whole new demographic to their membership that includes young families. Amongst this new membership many admitted that they never knew about the historical society before or had heard of it concluding that it simply wasn’t for them. Prior to this phenomenon, membership consisted almost exclusively of senior citizens who were largely interested in seeking genealogical information from the historical society’s research facilities. The farmers’ market also served thematically the 19th century offerings of the historic house; workshops in traditional crafts were eventually developed to coincide with market days.

Historical societies have other opportunities of making a greater connect with the public. Other opportunities might include providing “edutainment” like summer film festivals that include discussion forums. Viewing could be offered outdoors. With the number of local cable channels available today small museums might present some of their collection holdings in televised exhibits, which may include simply having a curator or scholar talk about an artifact that stands before them. Video tours of historical houses and sites and re-enactments could be the stuff of such cable programming.

Digital videotaping has made such a possibility affordable. Programming could also be assisted by cooperative partnerships with local schools, colleges, and budding historians and media production professionals. It seems logical that a local historical society could market itself by taking a more active role in the technologies that pose a threat to their own survival as a strong competitor for the time of the public.

The historical society could establish greater relevancy in the publics’ lives by actively participating in the current documentation of their community for future generations. How about collecting artifacts and narratives from more recent history rather than waiting until they become a rarity or nonexistent? A community’s history is a complex fabric of individual and group experiences so something like a reunion of local amateur garage bands from the 60s, 70s, and 80s might serve to attract more to the cause and mission of the historical society. Something as unique as re-uniting such bands and having them play for the community might be the lengths the historical society has to go to survive, for we have to ask ourselves who is it that is going to be preserving our community’s history after we’re gone? What will become of this chapter in history in an age of few letter writers and a preference for the extraordinary by the news gathering media of our time over the more commonplace experiences of us all. Will the unique character of our community survive for future generations to know and appreciate when so little of it is destined to be preserved?

Historical societies have an obligation to preserve our more recent history now. Broadening the scope of the artifacts and narratives collected and making use of digital media, which makes it possible to store huge amounts of information in a very small place that can be disseminated to the whole world, is among the important steps to take in marketing the historical society to more of the public. By doing this we can better insure that there will be someone to inherit this institution and meet the responsibility of both preserving the past and sharing it with future generations.

Robert Schmick is the Museum Director of The Curran Homestead; this position was made possible by a Davis Family Foundation grant. As a teacher of English language and literature for nearly 20 years, Schmick became interested in using archival and other primary source materials in writing curriculums. He received a Ph.D. from New York University in Arts and Humanities Education; his dissertation is entitled "A Wilderness For All: The Transmuting and Transmitting of Wilderness Imagery by Print Media and Material Culture for Antebellum America." He also received a Professional Certificate in Museum Studies and Administration from Tufts University that included an internship at the Addison Gallery of American Art at Phillips Andover. He has served as the Volunteer Director of Education for the Curran Homestead for the past year.

Successful marketing strategies are founded on an understanding of the public and their needs, or perceived needs. Small institutions, like the local historical society, need to step up to the plate and deliver new and attractive ways of presenting themselves. They must drive the point home that they are the real thing, a place where meaningful objects and trustworthy information can be found and serve a role in their lives and their community. In doing this they negate all the fears about taking on the agenda of marketing. They also need to embrace history of more than the elite of the past, present other periods in history than merely the distant past, and, finally, take on the untraditional role of documenting and presenting their community’s more recent past through the mediums of our own time---digital photography and audio in order to more effectively disseminate the information they have, namely much of their collections that are in storage for long periods of time, and become more relevant to generations that have embraced new digital media.

Taking on the point of view of visitors, or potential visitors, may mean that the local historical society must transcend merely the historical narratives of the 17th-19th centuries and seek to satisfy the current demand for twentieth century nostalgia by baby boomers, Gen-Xers, and the like. This could be a strategy that will result in drawing more people into the institution’s fold for further growth and initiate some needed enthusiasm among greater numbers for the historical society’s existing collections.

In saying this, I am reminded of institutions in which very dedicated individuals scratch their heads and wonder why they have so few younger and middle aged among their membership. Of course, this is a demographic that is busy raising families and working, but they do have leisure time, and the question the historical societies should be asking is how do we make our institution relevant to this group and make them want to spend that leisure as a visitor to our facility or involved in the collecting of local history and its dissemination through education.

What might be some of the specific marketing strategies that would make these historical societies more relevant to the lives of more? The Andover Historical Society (AHS) in Andover, Massachusetts has sought to reinvent how their community members come to know about what they offer. Not long ago they struck upon the idea of organizing a farmers’ market where one no longer existed. Small farms have sprung up in increasing numbers in the past few decades in this suburban community not far from Boston. A local high school student actually sparked the idea when she contacted AHS and asked whether there were any markets in the area to sell garden produce. AHS sent out feelers about the possibility of them creating a market on the small village lot that they own, and many local farmers were ecstatic about the idea.

The Historical Society provided rental space for these local farmers right next to the historical house they maintain. This situation has allowed for this institution to participate in the making of local history rather than merely preserving the long-ago past. This scheme not only resulted in added revenues but renewed interest in the historical society. As people came out to buy produce, they seized the opportunity to walk the grounds, ask questions about the historic house, and visit it. The historical society used the opportunity of having the public on their grounds on a regular basis for the purpose of buying produce to provide outdoor programming and events more frequently. There was significant free press coverage through this arrangement as well.

Through this scheme this historical society has attracted a whole new demographic to their membership that includes young families. Amongst this new membership many admitted that they never knew about the historical society before or had heard of it concluding that it simply wasn’t for them. Prior to this phenomenon, membership consisted almost exclusively of senior citizens who were largely interested in seeking genealogical information from the historical society’s research facilities. The farmers’ market also served thematically the 19th century offerings of the historic house; workshops in traditional crafts were eventually developed to coincide with market days.

Historical societies have other opportunities of making a greater connect with the public. Other opportunities might include providing “edutainment” like summer film festivals that include discussion forums. Viewing could be offered outdoors. With the number of local cable channels available today small museums might present some of their collection holdings in televised exhibits, which may include simply having a curator or scholar talk about an artifact that stands before them. Video tours of historical houses and sites and re-enactments could be the stuff of such cable programming.

Digital videotaping has made such a possibility affordable. Programming could also be assisted by cooperative partnerships with local schools, colleges, and budding historians and media production professionals. It seems logical that a local historical society could market itself by taking a more active role in the technologies that pose a threat to their own survival as a strong competitor for the time of the public.

The historical society could establish greater relevancy in the publics’ lives by actively participating in the current documentation of their community for future generations. How about collecting artifacts and narratives from more recent history rather than waiting until they become a rarity or nonexistent? A community’s history is a complex fabric of individual and group experiences so something like a reunion of local amateur garage bands from the 60s, 70s, and 80s might serve to attract more to the cause and mission of the historical society. Something as unique as re-uniting such bands and having them play for the community might be the lengths the historical society has to go to survive, for we have to ask ourselves who is it that is going to be preserving our community’s history after we’re gone? What will become of this chapter in history in an age of few letter writers and a preference for the extraordinary by the news gathering media of our time over the more commonplace experiences of us all. Will the unique character of our community survive for future generations to know and appreciate when so little of it is destined to be preserved?

Historical societies have an obligation to preserve our more recent history now. Broadening the scope of the artifacts and narratives collected and making use of digital media, which makes it possible to store huge amounts of information in a very small place that can be disseminated to the whole world, is among the important steps to take in marketing the historical society to more of the public. By doing this we can better insure that there will be someone to inherit this institution and meet the responsibility of both preserving the past and sharing it with future generations.

Robert Schmick is the Museum Director of The Curran Homestead; this position was made possible by a Davis Family Foundation grant. As a teacher of English language and literature for nearly 20 years, Schmick became interested in using archival and other primary source materials in writing curriculums. He received a Ph.D. from New York University in Arts and Humanities Education; his dissertation is entitled "A Wilderness For All: The Transmuting and Transmitting of Wilderness Imagery by Print Media and Material Culture for Antebellum America." He also received a Professional Certificate in Museum Studies and Administration from Tufts University that included an internship at the Addison Gallery of American Art at Phillips Andover. He has served as the Volunteer Director of Education for the Curran Homestead for the past year.

Monday, July 6, 2009

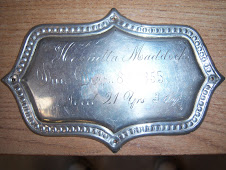

Mysterious Plates Found in the Wall of a Bangor House

Recently, I was talking with our barber as she clipped away at my son's hair. She shared how she came to find three mysterious plates with names and dates engraved on them. I talked her into digging them out so that I might get a look. In a house that she owned previous to the one she now owns, she came across the three metal plates shown at the right. Removing the plaster and lathe of the nineteenth century house near Ohio Street in Bangor, these were fished out in the same condition as they now appear a decade or so later. My guess is that the plates were once fastened to the coffins of those named on the plates, since they have holes in the corners of them and were obviously fastened to something.

If you recall, recent BHS guest speakers have shared their stories of finding coins dating from the initial and subsequent construction (s) of their eighteenth century homes in the process of renovating them. A shoe enclosed in the wall of eighteenth homes has also been said to have been a typical superstition and practice insuring a house's safety according to recent guest speakers. Finding what would seem to be casket plates in the walls of a nineteenth century is a new one for me? Insights about these plates, and how they might be typical or atypical of superstitions surrounding house construction from the time period would be greatly appreciated. Please email me at: rpschmick1@aol.com.

If you recall, recent BHS guest speakers have shared their stories of finding coins dating from the initial and subsequent construction (s) of their eighteenth century homes in the process of renovating them. A shoe enclosed in the wall of eighteenth homes has also been said to have been a typical superstition and practice insuring a house's safety according to recent guest speakers. Finding what would seem to be casket plates in the walls of a nineteenth century is a new one for me? Insights about these plates, and how they might be typical or atypical of superstitions surrounding house construction from the time period would be greatly appreciated. Please email me at: rpschmick1@aol.com.

"Junteenth Day"; An Annual Celebration to the End of Slavery (June 19, 1865), by David Hanna

A steady rain forced the fourth annual “Junteenth Day” celebration this past June 19th to be held in the Brewer Auditorium instead of at the Chamberlain Freedom Park of Brewer, Maine as scheduled. This designated day celebrates the end of slavery in the United States. On June 19, 1865, 2000 Union soldiers marched into Galveston, Texas at the end of the Civil War and enforced the tenets of the Emancipation Proclamation for the first time in the heart of the newly surrendered confederacy.

City of Brewer Mayor Arthur Verow read a proclamation recognizing the event, the spirit of self, and the long fight for freedom for African-Americans . He proclaimed June 19, 2009 as “Junteenth Day." In addition to Mayor Verow, State Representative Michael Celli, representatives from the offices of US Senator Olympia Snowe (Maine), US Senator Susan Collins (Maine), and US Congressional Representative Michael Michaud read statements praising the role of African-Americans in society and recognizing the tragedy of slavery as well as the importance of the “Underground Railway," a freedom trail for many slaves.

The keynote speaker was James Varner, president of the Maine Human Rights Coalition. He stated his goal was to get “Junteenth Day” officially recognized in the State of Maine as well as the nation noting that 31 states, along with the District of Columbia, had already done so. He spoke of the need to work diligently for the end of racism and discrimination in America.

City of Brewer Mayor Arthur Verow read a proclamation recognizing the event, the spirit of self, and the long fight for freedom for African-Americans . He proclaimed June 19, 2009 as “Junteenth Day." In addition to Mayor Verow, State Representative Michael Celli, representatives from the offices of US Senator Olympia Snowe (Maine), US Senator Susan Collins (Maine), and US Congressional Representative Michael Michaud read statements praising the role of African-Americans in society and recognizing the tragedy of slavery as well as the importance of the “Underground Railway," a freedom trail for many slaves.

The keynote speaker was James Varner, president of the Maine Human Rights Coalition. He stated his goal was to get “Junteenth Day” officially recognized in the State of Maine as well as the nation noting that 31 states, along with the District of Columbia, had already done so. He spoke of the need to work diligently for the end of racism and discrimination in America.

Wednesday, June 17, 2009

156 North Main Street, Brewer, Maine (circa 1877-8), Information Researched and Compiled by Dan Moellentin

Property originally owned by Penobscot Indians and then by John Holyoke

Property (still improved) consists of lot 29, 30, and westerly half of lot 31 from Treat's Lot Plan of Brewer, ME ( Joseph Treat, surveyor: Plan Book 1, pg. 42, titled "Plan of the Holyoke Place in Brewer at the South end of the Bangor Bridge as laid out into house and store lots under the direction of the heirs of John and Elizabeth Holyoke the 1st July 1833.

Distribution of Elizabeth Holyoke property in 1849: lots 29 and 30 went to calvin and Hanna Wiswell (Book 200, pg. 400, 1849) unimproved).

Hanna Wiswell sold lots 29 and 30 in 1874 to Caleb Hoyoke for $700.00 (unimproved): Book 445, pg. 198.

Caleb Holyoke sold lots 29 and 30 to Chas. M. Doane (not a relative of Holyoke family) in 1875 for $700.00: Book 461 pg. 334 ( no improvements shown on Comstock and Clinton printed map of 1875).

Chas. M. Doane sold lots 29 and 30 for $1000.00 in 1876 to Anie A. Hodgdon: Book 475, pg. 424---unimproved.

Amie A. Hodgdon and Samuel N. Hodgdon taxes on property show no homestead until 1878 where the real estate value is noted as $2100.00.

Style of exterior Mansard House as well as interior molding, fireplaces, and other characteristics indicate the house was likely built in 1877-8.

In 1886 triangle of land just west of lot 30 was purchased to widen access to North Main St.

1892? House and lots sold to Mary and Calvin M. Thomas for $1.00.

Mary thomas probate will in 1933 ( Book 1074, pg. 152) gave house to her children.

Property sold in 1947 to Joan and Lyman O. Warren Jr., a mortgage for $10,000 was obtained. Book 1247: pg. 224.

Property sold by Warrens in 1957 to Victor and Helen Emmel: Book 1273, pg. 224.

Property sold in 1970 to Paul and Joyce McKenney ( Book 1563, pg. 384) and mortgaged for $18,000: Book 2191, pg. 375.

Abnaki Council of the Girl Scouts of America bought property in 1990.

Property (still improved) consists of lot 29, 30, and westerly half of lot 31 from Treat's Lot Plan of Brewer, ME ( Joseph Treat, surveyor: Plan Book 1, pg. 42, titled "Plan of the Holyoke Place in Brewer at the South end of the Bangor Bridge as laid out into house and store lots under the direction of the heirs of John and Elizabeth Holyoke the 1st July 1833.

Distribution of Elizabeth Holyoke property in 1849: lots 29 and 30 went to calvin and Hanna Wiswell (Book 200, pg. 400, 1849) unimproved).

Hanna Wiswell sold lots 29 and 30 in 1874 to Caleb Hoyoke for $700.00 (unimproved): Book 445, pg. 198.

Caleb Holyoke sold lots 29 and 30 to Chas. M. Doane (not a relative of Holyoke family) in 1875 for $700.00: Book 461 pg. 334 ( no improvements shown on Comstock and Clinton printed map of 1875).

Chas. M. Doane sold lots 29 and 30 for $1000.00 in 1876 to Anie A. Hodgdon: Book 475, pg. 424---unimproved.

Amie A. Hodgdon and Samuel N. Hodgdon taxes on property show no homestead until 1878 where the real estate value is noted as $2100.00.

Style of exterior Mansard House as well as interior molding, fireplaces, and other characteristics indicate the house was likely built in 1877-8.

In 1886 triangle of land just west of lot 30 was purchased to widen access to North Main St.

1892? House and lots sold to Mary and Calvin M. Thomas for $1.00.

Mary thomas probate will in 1933 ( Book 1074, pg. 152) gave house to her children.

Property sold in 1947 to Joan and Lyman O. Warren Jr., a mortgage for $10,000 was obtained. Book 1247: pg. 224.

Property sold by Warrens in 1957 to Victor and Helen Emmel: Book 1273, pg. 224.

Property sold in 1970 to Paul and Joyce McKenney ( Book 1563, pg. 384) and mortgaged for $18,000: Book 2191, pg. 375.

Abnaki Council of the Girl Scouts of America bought property in 1990.

Friday, June 5, 2009

Summer Hours at the Brewer Historical Society's Clewley Museum, 199 Wilson Street, Brewer, ME

Our summer hours are 1-4 PM on Tuesdays and the fourth Saturday of the month (Spring and Fall 10-1 PM Tuesdays and also by appointment). The Brewer Historical Society's Clewley Museum is located at 199 Wilson Street, Brewer, Maine. Its mission is to maintain an educational museum to preserve Brewer's history for future generations.

Featured are exhibits about Joshua Chamberlain and unique items like a gramophone, grandfather clock, 19th and early 20th century photographs, and a dumb waiter, all set in this turn-of-the-century farm house. An adjacent shed features antique tools and a horse drawn hearse. Visit the upstairs children's room and military exhibits.

Also, stop by Chamberlain Freedom Park, Brewer's version of Little Roundtop battlefield at Gettysburg; it includes a cast metal statue of the hero of this decisive engagement, Brewer- native General Joshua Chamberlain. Experience at the park our nation's role in the Underground Railroad with the North to Freedom statue. The park is open year round and is located at the corner of North Main and State Street.

For more information mail: Brewer Historical Society, 199 Wilson Street, Brewer, ME 04412, or call: (207) 989-5013, or (207) 989-2693.

Featured are exhibits about Joshua Chamberlain and unique items like a gramophone, grandfather clock, 19th and early 20th century photographs, and a dumb waiter, all set in this turn-of-the-century farm house. An adjacent shed features antique tools and a horse drawn hearse. Visit the upstairs children's room and military exhibits.

Also, stop by Chamberlain Freedom Park, Brewer's version of Little Roundtop battlefield at Gettysburg; it includes a cast metal statue of the hero of this decisive engagement, Brewer- native General Joshua Chamberlain. Experience at the park our nation's role in the Underground Railroad with the North to Freedom statue. The park is open year round and is located at the corner of North Main and State Street.

For more information mail: Brewer Historical Society, 199 Wilson Street, Brewer, ME 04412, or call: (207) 989-5013, or (207) 989-2693.

Tuesday, May 26, 2009

Author Wilbur Wolf Will Share His Memoir of a Farm Boy at The Curran Homestead Living History Farm and Museum on Thursday, May 28, 2009 at 6:30 PM

As the first in a series of public oral histories at The Curran Homestead, author Wilbur Wolf, of Orlond, ME, will be offering signed copies of his Memoir of a Farm Boy as well as sharing some of its details in this talk and slide presentation at The Curran Homestead Living History Farm and Museum, Fields Pond Rd., Orrington on May 28 at 6:30 PM. Wolf’s book, which was originally conceived as a memoir for his children, documents his family farm experiences in the 1930s and 1940s. Beginning with the almost two hundred year history of his parents’ upstate New York dairy, he offers details of early mechanization, animal husbandry, small town life, and poignant human relations in a rural community of the past.

According to Dr. Robert Schmick, Volunteer Director of Education at The Curran Homestead, “Wolf’s experiences are becoming more unique with each passing day in America as small family farms are consumed by corporate owned agro-businesses and many more are simply re-purposed for residential subdivisions and strip malls. It is not that the times that Wolf writes of were simpler; it is that there was a close knit community on hand to comfort people during good and bad times, people discovered their own entertainments, and there was both a necessity and personal pride in earning a living from the land and ones own industry that is no longer commonplace. There were a greater number of farms per capita in Maine and the rest of the US, and people not only had the ability to grow more of their own food but supply their local community with lower cost staples not tethered to world petroleum prices.”

Schmick added that “it is our mission at The Curran Homestead to preserve the traditions of the family farm, self-reliance, and ingenuity which were part of Wolf’s experiences, and through continued public talks like this we hope to both preserve a bit of this past so that it may continue to mold future generations. Come pick up a copy of Memoir of a Farm Boy, have it signed, and chat with its author Wilbur Wolf. Wilbur may even play a tune or two on one of our early pipe organs after the talk. Coffee and homemade cooked rhubarb on shortbread will be served. Admission is free, but we are an all-volunteer non-profit organization and would appreciate your donations.

According to Dr. Robert Schmick, Volunteer Director of Education at The Curran Homestead, “Wolf’s experiences are becoming more unique with each passing day in America as small family farms are consumed by corporate owned agro-businesses and many more are simply re-purposed for residential subdivisions and strip malls. It is not that the times that Wolf writes of were simpler; it is that there was a close knit community on hand to comfort people during good and bad times, people discovered their own entertainments, and there was both a necessity and personal pride in earning a living from the land and ones own industry that is no longer commonplace. There were a greater number of farms per capita in Maine and the rest of the US, and people not only had the ability to grow more of their own food but supply their local community with lower cost staples not tethered to world petroleum prices.”

Schmick added that “it is our mission at The Curran Homestead to preserve the traditions of the family farm, self-reliance, and ingenuity which were part of Wolf’s experiences, and through continued public talks like this we hope to both preserve a bit of this past so that it may continue to mold future generations. Come pick up a copy of Memoir of a Farm Boy, have it signed, and chat with its author Wilbur Wolf. Wilbur may even play a tune or two on one of our early pipe organs after the talk. Coffee and homemade cooked rhubarb on shortbread will be served. Admission is free, but we are an all-volunteer non-profit organization and would appreciate your donations.

Monday, May 4, 2009

Ice Houses Along Penobscot Not Forgotten, by Howard F. Kenney

Ice Making

In our recollection of industries which once played a part in the history of Bangor-Brewer, we cannot overlook the ice industry. Reaching its peak in the late 1800s, the ice harvest was one of the major industries in Brewer. Records show that when this business was at its peak, in the more prosperous years, a harvest of 300,000 tons was taken from the river.

Ice houses lined the river from the “ferry place” to the Narrows. On the Brewer side were: a small one just above the old bridge, one which was located at the site of Smith’s Planing Mill, the E. and J.K. Stetson ice house near the ferry boat slip; the Getchell Brothers and the Hill and Stanford houses near the site of the old Dirigo Mill (formerly O. Rolnick & Son site, since torn down); the American Ice Company houses near the old eastern Ball park; the Sargent Lumber Company ice house near the Orrington Ice Company; and the Arctic and American houses near the narrows of the river.

Dan Sargent was a pioneer in the ice harvesting business. The largest of the houses harvested from 25,000 to 30,000 tons of ice during the winter. In the years when the Hudson River [New York] produced a poor crop of ice, there was such a demand for ice from the Penobscot River that local ice companies also harvested from Green Lake and Phillips. The many saw mills along the river furnished sawdust, which made excellent packing for the ice in transit to prevent its melting.

Getchell Brothers first appeared in the records in 1900, although it was established in 1888 by Fred and J. Calvin Getchell. It had a Bangor location at 17 State St. and a Brewer location at 101 Wilson St. By 1920 Getchell Brothers reigned supreme and alone. In those days, the ice cart, drawn by two horses, plodded casually along the street, the cart’s bright yellow painted sides calling attention to its wares.

The cart stopped at houses of those people who were fortunate enough to have a refrigerator, and an ‘ice card” in the window. The iceman would stop, haul a large cake of ice to the back of his cart, chop off the desired amount, swing it over his black-rubber covered back, and stride off for the customer’s house. The customers had a card which had four corners, one for each amount: 25, 50, 75 and 100. The corner at the top was the number of pounds desired, when placed in the window. There were always several children hovering at the back of the cart, ready to pick up the pieces of ice that were lost in the process of chopping---a delightful treat on a hot summer day.

During the summers of their high school days, in the 1920s, many high school students used to work on Getchell’s ice wagons, delivering up to 100 pounds of ice per load on their backs. This work served a two-fold purpose. First, it helped them build up their bank accounts. Secondly, the nature of this rugged labor helped to build up their muscles and condition them for fall football encounters.

More on Ice Making

We will begin our story around 1879, with a tour of D. Sargent & Sons ice-making plant, the most accessible. We begin by taking the electric car to their plant, which is opposite the American Ice Company, on the Bangor side of the river.While on our way to the ice house, we fall in the company of the Hon. H.P. Sargent, senior partner of the firm, who takes us and pilots us to the foot of the elevator and shows the manner in which the ice cakes are taken from the eater and carried, at the rate of 25 to 30 cakes per minute, up the elevator to various runs to the houses. Following on the side of the canal, we go into the head of the ice field where we meet field foreman Frank Young, for much information about work and statistics.

Harvesting Ice

The first thing to do in the ice industry is to find your ice. Upon freezing over of the river the owners of the various ice plants stake out their several fields and if snow falls, as soon as the ice is sufficiently strong, men and horses remove the snow with long scrapers and bring it ashore. This is done for two reasons: first that the cold may come in contact with the ice and freeze it more quickly and to a greater thickness, and second, that its weight may not sink the ice and cause the water to flow over it, forming slush and snow ice. It is the latter condition which has caused the travelling on upper Moosehead Lake to be so bad in the winter. Ordinarily the ice is ready to harvest by the first of January and the season covers a total of a month to six weeks, so that our ice men should have the ice houses filled.

How it is done

When the ice is ready to be cut, it is run in a line with a hand marker, an ice plow on a small scale, a large marker is used, a gauge, running in the channel first made, making a cut 32 inches from the first. In this manner the whole field is marked out as far as wanted. Next, after the marker, follows the plow drawn by two horses, which adds about three inches in depth to the three inches already made. This in turn is followed by another run which makes the cut from nine to 12 inches in depth according to the thickness of the ice. The same thing is done at right angles to the first line. The difference is that the second lines are 22 inches apart, making an oblong cake 32 by 22 inches and of such of clear ice, not less than 12 inches, as the ice will make.

If the cutting of commences, as it did at Sargent’s, at some distance from the foot of the elevator, a 42-inch wide canal is cut out to the field and through this the ice is pushed by men with pickaroons as rapidly as it can be taken up by the elevator. The elevator carries about one cake to every eight feet in length of the circular chain. The elevator can be arranged, as was that of the American Ice Company, to carry two cakes together instead of one and this greatly increases the daily output, or perhaps input. After a sufficient quantity of ice has been removed to make [a] sea roon [sic?] [canal], the field of ice is divided into large flows, containing some 400 cakes, or 50 tons of ice, by separating it at the ends from the mass by the use of peculiar double ice-chisel.

Running the elevators

These ice floes are then floated down to a wide channel where they are divided, as may perhaps be best expressed, into a dozen cakes of ice side by side, and as these are run through the narrow canal first mentioned, men with chisels divide the cakes from each other at the same time that the other men are pushing them along to the elevator when they arrive, one close to the other, to be taken up by the lugs of the elevator and carried up to such an elevator for the tour of inspection. As each cake of ice enters the elevator it passes under a knife, the blade of which resembles the cutter of a mowing machine, which removes the snow ice and cuts the cakes to a uniform depth of 12 inches---at the present thickness of the ice---that being the minimum thickness allowed.

Runs, constructed of hard wood bars stretching lengthwise with sides to prevent the ice from coming off the track, are extended into the houses at various heights. Commencing with the lower runs and continuing to the upper, the cakes, are urged on their slightly descending course by a little army of men nimbly using their picks. They are sluiced into the houses and upon the other runs by which they are conveyed all over the houses. Here the crystal cakes are packed side by side, with a little space between to prevent them from freezing into a solid mass.

It is lively work and each part of the operation goes on simultaneously, the force of men being so divided that nobody has to wait on another. It may well be to say, for the benefit of those not familiar with the business, that after the houses are filled and the entrances closed up and the space between the inner and outer layers filled with sawdust, a coating or dunnaging of hay is spread over the ice.

The first authentic account of ice being shipped from Maine, as stated in the report of Commissioner of Industrial and Labor Statistics, was in 1826, when the brig Orion of Gardiner, which had lain frozen in the Kennebec River during the winter, was loaded with the floating ice when the river broke up in the spring. The cargo was taken to Baltimore and sold for the sum of $700. In that year a house of 1,500 tons capacity was erected on Trott’s Point, Hallowell. It was filled, and, on the following summer, its contents was shipped to Southern and West India ports. The speculation proved unprofitable, and the business was abandoned after some years. In 1831 the Tudor Ice Company of Boston refilled this building and erected another in Gardiner, housing 3,000 tons during the season.

In 1849 Mr. W.H. Lawrence of Gardiner constructed an ice plow with one cutting tooth and guides, which proved of great benefit, and was the original of the improved and finely constructed plows now in use. Indeed, in every part of the work, the progress has been great, and improved machinery and tools, and experience in the work have reduced the cost of harvesting to a minimum by enabling the largest amount to be handled in the shortest period of time.

Ten Years Ice Harvest (Tons) on the Penobscot River

Year

1881 81,000

1882 146,000

1883 112,000

1884 58,500

1885 104,500

1886 176,000

1887 151,000

1888 200,000

1890 506,300

Then and Now

In earlier times, whip saws cut out the cakes, two feet by four, and men slowly dragged them up an incline to the houses by oxen. Now the plow rapidly cuts the cakes 22 X 32 inches, and these are taken by steam elevator into the houses at the rate of 25 cakes to 50 a minute. The American Ice Company, in this city, putting it in at the latter rate, produced an average of 2,500 tons a day. There was but a moderate increase of production on the Kennebec up to 1860; the business in Maine being confined to that river up to that time. Quite a boom was then had, owing to the failure of the crop in the South, and new and more or extensive and permanent plants were established. Rapid progress was made and a flourishing business done for five to six years, following, and since that time the business has been active, and an immense business has been done.

On the Penobscot

The first ice plant on the Penobscot was prior to 1871, at Rockport, when the Carltons and Rockport Ice Co. went into business. In that year H.E. Pierce, of Belfast, also entered. The first housing for shipment from Bangor below the dam, was 1879 and 1880, when D. Sargent & Sons, Rollins & Arey, and E. & J.K. Stetson were among the first to lead off, and they have continued.

Loading the Vessels

Shipments usually commence with our regular dealers as soon as the ice has left the river. The new crop is desired by the customers, and the early cargoes are hurried off. The handling of ice yearly improves. In our early history, 75 tons was a good day’s work. During the past summer, several of the crews have handled 1,000 tons in 10 hours. The ice is taken from the ice house now in a uniform manner of working, with runs, chisels, and starting bars. About three layers are removed together, first the top, then the middle, and then the bottom. It is carried on ice runs to the vessels mostly by hand, yet many now employ steam power, with a carrying chain to convey it. Ice tongs and ropes were employed previous to 1890, dropping the ice into holds of the vessels. In that year, M.R. Shepard & Ballard, of the Knickerbocker Ice Co., invented the automatic vessel loading machine, which is now in general use. A platform dropping two blocks is employed, making quick work, and meeting a long felt want. In early days of the industry 75 tons was considered a good day’s work.

Friday, April 24, 2009

The Brick Story, by Howard Kenney

There is an old saying in these parts that Boston was built of Bangor lumber and Brewer brick. And it is an easily demonstrable truth. Not only is Boston extant and Maine’s tall timber gone, but Brewer actually lies in a series of hollows left by the excavation of its clayey earth, which was pressed and fired into those bricks which nowadays compose so much of structural Boston. Indeed, as charming a school and athletic field as you can imagine lies in one of these natural amphitheaters.

During the early days of Brewer, brick making was one of this city’s major industries, and “Brewer made brick” was shipped out many miles and had an excellent reputation for quality. We can remember when the “brickyard flats”; where bricks were spread to dry after being “burned” or baked, made excellent baseball diamonds when not covered with drying brick. In fact, the last brickyard in Brewer, Brooks brick Yard, stopped making bricks in 1956, and since that time, the Brooks Brick Company has operated as brokers, importing bricks from brick makers in Maine, Massachusetts, Ohio, and other states, as well as Canada.

So let’s get to Brewer brick making from the start.

Some of the geographical contours of Brewer can be traced directly to the days when brick making was a very important industry. The working of these yards, one authority says that they were twenty at one time, caused the cutting away of many hills. One notable example of this is The Bucksport Branch of the Maine Central railroad. The tracks follow these cuts from Main to Jordan Streets. The Athletic Field and the Auditorium are located on the site of an abandoned brickyard, believed to be John Holyoke’s. We also find a Dunn’s brickyard mentioned, and a brickyard on the Farrington farm.

Several of Brewer’s early industries cooperated to make a fine vessel load for shipping. Lumber was stowed below deck with the brick on top of that. Then the bales of hay were loaded on top of the brick and the whole thing was covered with canvas to protect it from the weather. Ships carrying these articles as cargo , brought back coal , pig iron, and cement.

It is documented that at one time seventeen brickyards used 3000 cords of wood a year. The brick making season was generally from May to September. One Mr. Holyoke, who owned a brick yard, stated that if he began at the earliest point, he could make the first ready by July. In Maine, the brick export business was at its peak in the early 1850s. The Civil War checked the business for a number of years, but business picked up again until the 1880s.

Of the number of bricks burnt at one time, which was between 250,000and 900,000, only about one percent were found to be unsalable. Usually, seven men were employed steadily, with extra help called in when it was needed. The men worked from 5AM to 7PM, with the necessary amount of time allowed for three meals. Many Irish laborers were employed in the brickyards. It took about nine days for a burn to be completed. We remember the active days of the Brooks Brick Company, when a red glow in the sky would strike terror in the heart, to be relieved almost immediately when we realized it was only the burning of the kiln.

Water for making brick was taken from a small brook near the Holyoke Brick Yard. This yard used about 2000 gallons of water a day. This brook has become part of the City’s sewer system, and cannot be seen today.

An item, dated February 12, 1900 states that on a Saturday, the largest load of wood hauled into Brewer, was brought from Holden Center for William Burke’s Brick Yard. It was hauled by a pair of horses owned by George Hinman, of South Brewer, and measured three and a half cords. The Brewer Brick Cart originated here. It was a four wheeled cart with straight axles. The hind wheels were larger than the fore. The entire weight balanced on the hind wheels. The cart could be turned. The front was hooked down but when released, would let the cart body tip up in front, thus allowing the brick to run out.

It has been said that for a time the US Government used Brewer brick for a standard. At that time, all government orders were written “to be constructed of Brewer brick, or the equal.” These bricks were made from fine gray clay, and seemed to have an indefinite lifetime. A shipload of bricks was from 35,000 to 55,000. The rate on shipping bricks to North Carolina was cheaper than it was to Boston. The reason for this was that bricks were in demand for ballast on ships that carried hay to North Carolina. However, a great many of the bricks were shipped to Boston where they were sold at auction on the market by commission merchants.

Brick making in Maine is said to have begun at almost the same time that settlement began. Apparently, there was brick made for shipment before the middle of the eighteenth century by some parts of the District of Maine. One reason for large shipments to Boston was that it required buildings of brick construction rather than the wood that had been used for its earliest structures. Many sections of the city were situated below grade and prone to continual dampness; wood structures would quickly rot whereas brick insured greater longevity for buildings hence greater profitability. The rebuilt section of Boston is said to have been constructed almost entirely of Brewer brick.

In 1867, about a dozen companies were making brick; one of the larger producers was the Brewer Steam Brick Company. There was a great demand for Brewer brick all over New England, but it was also being shipped to North Carolina, Florida, Texas, and the West Indies, and Newfoundland on a regular basis.

The building material in the Good Shepherd Convent in Van Buren, and in Bangor City Hall (the old one) had its origin here. The brick used in the old Bangor YMCA were hand pressed and made in Frank Graten’s Yard. Some old notes have been found that document Fort Sumter’s construction with Brewer brick. This is likely, given that large numbers of brick were shipped to this region during the time of the Fort’s construction.

In 1902, the year the middle span of the Bangor-Brewer Bridge was washed out; a Brewer brick yard had the contract to finish the brick for the Bangor Court House. At that time a temporary bridge was improvised so that travel between the two cities might not be cut off. Mr. Harrison Brooks and the Littlefield family have long been names that were connected with brick making in Brewer through their joint ownership of the Brooks Brick Company.

Now the brick making machinery is silent. The brick cart stands empty and disconsolate, and the sky above Brewer no longer glows with the flames from its long burning kilns.

During the early days of Brewer, brick making was one of this city’s major industries, and “Brewer made brick” was shipped out many miles and had an excellent reputation for quality. We can remember when the “brickyard flats”; where bricks were spread to dry after being “burned” or baked, made excellent baseball diamonds when not covered with drying brick. In fact, the last brickyard in Brewer, Brooks brick Yard, stopped making bricks in 1956, and since that time, the Brooks Brick Company has operated as brokers, importing bricks from brick makers in Maine, Massachusetts, Ohio, and other states, as well as Canada.

So let’s get to Brewer brick making from the start.

Some of the geographical contours of Brewer can be traced directly to the days when brick making was a very important industry. The working of these yards, one authority says that they were twenty at one time, caused the cutting away of many hills. One notable example of this is The Bucksport Branch of the Maine Central railroad. The tracks follow these cuts from Main to Jordan Streets. The Athletic Field and the Auditorium are located on the site of an abandoned brickyard, believed to be John Holyoke’s. We also find a Dunn’s brickyard mentioned, and a brickyard on the Farrington farm.

Several of Brewer’s early industries cooperated to make a fine vessel load for shipping. Lumber was stowed below deck with the brick on top of that. Then the bales of hay were loaded on top of the brick and the whole thing was covered with canvas to protect it from the weather. Ships carrying these articles as cargo , brought back coal , pig iron, and cement.

It is documented that at one time seventeen brickyards used 3000 cords of wood a year. The brick making season was generally from May to September. One Mr. Holyoke, who owned a brick yard, stated that if he began at the earliest point, he could make the first ready by July. In Maine, the brick export business was at its peak in the early 1850s. The Civil War checked the business for a number of years, but business picked up again until the 1880s.

Of the number of bricks burnt at one time, which was between 250,000and 900,000, only about one percent were found to be unsalable. Usually, seven men were employed steadily, with extra help called in when it was needed. The men worked from 5AM to 7PM, with the necessary amount of time allowed for three meals. Many Irish laborers were employed in the brickyards. It took about nine days for a burn to be completed. We remember the active days of the Brooks Brick Company, when a red glow in the sky would strike terror in the heart, to be relieved almost immediately when we realized it was only the burning of the kiln.

Water for making brick was taken from a small brook near the Holyoke Brick Yard. This yard used about 2000 gallons of water a day. This brook has become part of the City’s sewer system, and cannot be seen today.

An item, dated February 12, 1900 states that on a Saturday, the largest load of wood hauled into Brewer, was brought from Holden Center for William Burke’s Brick Yard. It was hauled by a pair of horses owned by George Hinman, of South Brewer, and measured three and a half cords. The Brewer Brick Cart originated here. It was a four wheeled cart with straight axles. The hind wheels were larger than the fore. The entire weight balanced on the hind wheels. The cart could be turned. The front was hooked down but when released, would let the cart body tip up in front, thus allowing the brick to run out.

It has been said that for a time the US Government used Brewer brick for a standard. At that time, all government orders were written “to be constructed of Brewer brick, or the equal.” These bricks were made from fine gray clay, and seemed to have an indefinite lifetime. A shipload of bricks was from 35,000 to 55,000. The rate on shipping bricks to North Carolina was cheaper than it was to Boston. The reason for this was that bricks were in demand for ballast on ships that carried hay to North Carolina. However, a great many of the bricks were shipped to Boston where they were sold at auction on the market by commission merchants.

Brick making in Maine is said to have begun at almost the same time that settlement began. Apparently, there was brick made for shipment before the middle of the eighteenth century by some parts of the District of Maine. One reason for large shipments to Boston was that it required buildings of brick construction rather than the wood that had been used for its earliest structures. Many sections of the city were situated below grade and prone to continual dampness; wood structures would quickly rot whereas brick insured greater longevity for buildings hence greater profitability. The rebuilt section of Boston is said to have been constructed almost entirely of Brewer brick.

In 1867, about a dozen companies were making brick; one of the larger producers was the Brewer Steam Brick Company. There was a great demand for Brewer brick all over New England, but it was also being shipped to North Carolina, Florida, Texas, and the West Indies, and Newfoundland on a regular basis.

The building material in the Good Shepherd Convent in Van Buren, and in Bangor City Hall (the old one) had its origin here. The brick used in the old Bangor YMCA were hand pressed and made in Frank Graten’s Yard. Some old notes have been found that document Fort Sumter’s construction with Brewer brick. This is likely, given that large numbers of brick were shipped to this region during the time of the Fort’s construction.

In 1902, the year the middle span of the Bangor-Brewer Bridge was washed out; a Brewer brick yard had the contract to finish the brick for the Bangor Court House. At that time a temporary bridge was improvised so that travel between the two cities might not be cut off. Mr. Harrison Brooks and the Littlefield family have long been names that were connected with brick making in Brewer through their joint ownership of the Brooks Brick Company.

Now the brick making machinery is silent. The brick cart stands empty and disconsolate, and the sky above Brewer no longer glows with the flames from its long burning kilns.

Thursday, April 2, 2009

Author Wilbur Wolf at The Curran Homestead's 13th Annual Maple Syrup & Irish Celebration on Saturday, April 4, 10AM-2PM

At The Curran Homestead Living History Farm and Museum’s 13th Annual Maple Syrup and Irish Celebration, Saturday, April 4 , 10AM-2PM, , author Wilbur Wolf will be offering signed copies of his new book Memoirs of a Farmboy. Wolf will discuss and answer questions about the almost two hundred year history of his family’s farm highlighting his experiences growing up on the small dairy in Upstate New York during the 30s through the 50s. According to Dr. Robert Schmick, Volunteer Director of Education, “such experiences are becoming more unique with each passing day in America as small family farms are consumed by corporate owned agro-businesses and many more are simply re-purposed for residential subdivisions and strip malls,” so pick up a copy of this book, have it signed, and help support The Curran Homestead Living History Farm and Museum in its mission to preserve one Maine family farm and keep the experiences of Maine rural life alive for present and future generations.

Saturday, April 4, from 10AM-2PM, has been declared the date of the 13th Annual Curran Homestead Maple Festival & Irish Celebration Day by John Mugnai, President of the Living History Farm and Museum Board of Directors. The Curran Living History Farm and Museum on Fields Pond Road in Orrington will come to life with shared yarns spun about the good ole days around the wood burning stove. Meet Bodica and Mulls, the shaggy haired Scottish Highland cows and some lambs too. Enjoy an Easter egg hunt with the kids. Experience an ongoing demonstration of how to make maple syrup. Taste maple syrup, maple sugar baked beans, and corn chowder. Savor Cathy Martinage’s Irish stew (its main ingredient courtesy of Dan Hughes’ A Wee Bit Farm) and her Irish soda bread too. Sing along to the Irish folk music of Jerry Hughes. Also, meet Hugh Curran, an expert on Celtic culture, mythology, and spirituality. This event promises to be a step back in history to a simpler time of food, fun, and entertainment on the farm with the whole community invited. Event admission for members and donors is $5 per adult and $3 per child (under 12). For non-members, admission is $7 per adult and $5 per child (under 12), and this includes refreshments and participation in all events.

Saturday, April 4, from 10AM-2PM, has been declared the date of the 13th Annual Curran Homestead Maple Festival & Irish Celebration Day by John Mugnai, President of the Living History Farm and Museum Board of Directors. The Curran Living History Farm and Museum on Fields Pond Road in Orrington will come to life with shared yarns spun about the good ole days around the wood burning stove. Meet Bodica and Mulls, the shaggy haired Scottish Highland cows and some lambs too. Enjoy an Easter egg hunt with the kids. Experience an ongoing demonstration of how to make maple syrup. Taste maple syrup, maple sugar baked beans, and corn chowder. Savor Cathy Martinage’s Irish stew (its main ingredient courtesy of Dan Hughes’ A Wee Bit Farm) and her Irish soda bread too. Sing along to the Irish folk music of Jerry Hughes. Also, meet Hugh Curran, an expert on Celtic culture, mythology, and spirituality. This event promises to be a step back in history to a simpler time of food, fun, and entertainment on the farm with the whole community invited. Event admission for members and donors is $5 per adult and $3 per child (under 12). For non-members, admission is $7 per adult and $5 per child (under 12), and this includes refreshments and participation in all events.

Friday, March 13, 2009

Guest Speaker Brent Phinney Shares Brewer's Wood Shipbuilding History

As many who are local to the area know, one of the major defeats of the Continental Navy during the American Revolution occurred right on the Penobscot between Castine and Brewer. The story goes that Continental forces had planned to recapture Castine from the British. Some four hundred soldiers under the cover of fog attacked British fortifications at Castine resulting in their enemy’s hasty retreat.

The land assault was to be followed up by a naval attack under the command of Commodore Dudley Saltonstall of New Haven, CT, but the opportunity was missed when he “stubbornly refused to fight, opposed demanding surrender, and would not cooperate with the lands forces ” (Smith 234). The land forces gained ground threatening the British position while Saltonstall, with a naval force of nineteen armed vessels and twenty four vessels, most privately owned and piloted, remained at a safe distance and fired his cannons. After two weeks of holding this position, Sir George Collier with a force of seven ships maneuvered in range of Saltonstall and fired a broadside.

Avoiding any chance of loss or seizure of their private property, the interests of the privateers aiding the Continental Navy took precedence over any obligation they felt to the patriot cause; they retreated from Collier’s attack. The Continental Navy and Army's position immediately deteriorated resulting in an order to scuttle both vessels and transports, regardless of who owned them, in order to keep them out of the hands of the British. Some vessels were run aground, blown-up, or set afire while some fled up the Penobscot under pursuit.

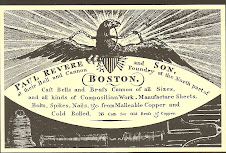

Land forces scattered and were forced to retreat through dense forest, and many soldiers subsequently died from hunger and exposure during their flight to safety. Some of the fleet made their way to a point between Brewer and Bangor where they were burned to the waterline and sunk. As a result of these losses, Saltonstall faced a court martial and was ordered to never hold a commission again while other participants in the failed land attack, including Paul Revere who commanded the ordinance, were honorably acquitted.

Two hundred plus years later our guest speaker Brent Phinney located the remains of one of Saltonstall’s fleet while scuba diving for the remains of the nine vessels of this fleet known to have gone down in the vicinity of Brewer and Bangor. The location of the surviving hull is about midway between the location of the Muddy Rudder Restaurant on the Brewer side and the harbor master’s office on the Bangor side of the river. The discovery resulted in the honor of having this site declared on later US Navy mapping as the “Phinney Site.”

Remarkably timbers, cannon balls, and other defining artifacts remained at the bottom of the river at a fortuitous position near the shore; it was fortuitous because this wreck had largely escaped the severe churning and abrasive nature of winter ice flows of the Penobscot for over two hundred years. This phenomena, Phinney theorizes, likely swept away the remains of the eight other Continental Navy vessels known to have been scuttled.

The wreck is in every sense of the word that, a wreck, for much of what remains is everything below the ship’s original waterline, and this lay largely buried under sediment. There are charred timbers visible that have undoubtedly survived decay because of that circumstance alone. A US Navy survey over the course of four consecutive summers by student divers recovered and photographed many artifacts at the site. Undoubtedly the BHS would be interested in obtaining some copies of those photographs for its own archives.

One of the greatest finds at the site occurred when Phinney himself accompanied the US Navy divers. As an expert on local ship building, be was aware that ship builders often placed a coin under a hollowed out spot on the mast deck before mounting the main mast of a ship. This was considered a talisman. The mast of this wreck had long since been destroyed or displaced but after removing sediments from its original position there lay the oxidized coin. It was later revealed after cleaning to be a 1708 Spanish silver coin. Phinney shared a photograph with the BHS that illustrated the remarkably good condition of the obverse and reverse of the coin. This find remains with all other objects recovered from the site under US Navy stewardship.

A testing of wood samples from the wreck confirmed that this particular vessel was constructed of trees from what is now the State of Maine. Maine, particularly Brewer and Bangor, were responsible for some 161 large wooden vessels during their tenure as premier ship building locations until 1919. In that year, which also marked the armistice of “the war to end all wars,” the building of large four mast sail boats ended with the launching of the last of its kind, the 1000 ton, 210 foot Horace Munroe. The occasion was marked by a dramatic mishap when the schooner slid down its rail faster than expected during the launch, and seamen missed their opportunity to drop anchor. The schooner raced across the Penobscot crashing into the McLaughlin & Company warehouse on the Bangor shore. It had to be towed back to Brewer and repaired.

From 1849-1919 there were four major shipyards producing barkentines, schooners, and other types of sailcraft on the Brewer shoreline. These shipyards changed hands a few times during this seventy year period, but Cooper and Dunning, McGilvery, which was later E. and I.K. Stetson, Gibbs and Phillips, Barbour, and Oakes were among the most prominent. The site of the McGilvery shipyard is currently Brent Phinney’s own steel shipbuilding enterprise. Unlike his antecedents he constructs boats using I-beams and metal plating as well as using modern hydraulics for dry-docking and launching the boats in his yard. His projects are usually limited to 65 feet in length weighing anywhere between 90 and 300 tons.

In days of yore elaborate wooden scaffolding was part of the formula for creating and launching wooden vessels. A wooden rail was lubricated with bear’s grease to insure a smooth glide down to the river’s surface. Oxen and horses were employed in these constructions as well. Seventy five men usually took a year to a year and a half to transform the hand shaped wooden timbers and wrought iron spikes and hardware into a seaworthy vessel. There was no better place for making wooden ships, for Maine is blessed with one of the greatest wood supplies that the world has ever known. Local sapwoods like hacmatack and hardwoods like oak were especially important to boat construction. Local brickyards also supplied brick ballast for these ships.

Phinney has put together a small museum gallery at his office on the Brewer shoreline; here are framed pictures of the Horace Munroe and Charles D. Sanford, which was launched in 1918, among many others. The latter ship also encountered difficulties at its launching sticking fast to the rail during its send off, and the launch was postponed for another day. In 1874, the Claire McGilvery must have displaced much water weighing in at 1329 tons at the McGilvery shipyard. William McGilvery had begun shipbuilding in Searsport, but by 1867 the barkantine Manson was launched from his Brewer site marking decades more of successful ship production.

In addition to photos, Phinney shared some of the tools of the trade of shipbuilding, including an adze, an early rotary measure, and a right-handed axe that had come down through his family by way of a great uncle in Steuben who had been a shipwright. During Phinney’s restoration of the shoreline of his property and while digging footings for a new building on the site, he has uncovered layers of shipbuilding activity below the surface. Among dense wood shavings and sawdust, these layers have produced numerous wrought iron spikes and wood staples once used for joining wood ship timbers. There are also numerous metal files which Phinney reckons were used for sharpening all the hand tools used daily during ship construction.

Phinney also brought with him a wood knee that would have been familiar and numerous in a shipyard in the past but would likely puzzle some of us today on what its purpose had once been. Used for supporting decking as well as for reinforcing corners, these hand carved components were made from hacmatack. According to Henry Wiswell, President of the Orrington Historical Society and attendee, local farmers would produce such components themselves and sell them to local shipyards for extra money; he has family records that rate the cost of a ship knee at a dollar apiece in the first half of the 19th century.

Such artifacts inspired much thought about the shear manpower, magnitude, and ingenious methods employed on these solely wooden constructions as Phinney's antique shipwright's tools and vintage photos were passed around the room by BHS members and the general public in attendance this past Tuesday, March 3 evening. We are fortunate that we have Brent Phinney to collect what information and material culture he can from this important chapter not only in Brewer history but the nation’s own, and share it with us in person and through its preservation as a recording in our ever-evolving oral history archive.

References

Smith, Marion Jaques. A History of Maine; From Wilderness To Statehood. Portland, ME: Falmouth Publishing House, 1949.

The land assault was to be followed up by a naval attack under the command of Commodore Dudley Saltonstall of New Haven, CT, but the opportunity was missed when he “stubbornly refused to fight, opposed demanding surrender, and would not cooperate with the lands forces ” (Smith 234). The land forces gained ground threatening the British position while Saltonstall, with a naval force of nineteen armed vessels and twenty four vessels, most privately owned and piloted, remained at a safe distance and fired his cannons. After two weeks of holding this position, Sir George Collier with a force of seven ships maneuvered in range of Saltonstall and fired a broadside.

Avoiding any chance of loss or seizure of their private property, the interests of the privateers aiding the Continental Navy took precedence over any obligation they felt to the patriot cause; they retreated from Collier’s attack. The Continental Navy and Army's position immediately deteriorated resulting in an order to scuttle both vessels and transports, regardless of who owned them, in order to keep them out of the hands of the British. Some vessels were run aground, blown-up, or set afire while some fled up the Penobscot under pursuit.

Land forces scattered and were forced to retreat through dense forest, and many soldiers subsequently died from hunger and exposure during their flight to safety. Some of the fleet made their way to a point between Brewer and Bangor where they were burned to the waterline and sunk. As a result of these losses, Saltonstall faced a court martial and was ordered to never hold a commission again while other participants in the failed land attack, including Paul Revere who commanded the ordinance, were honorably acquitted.

Two hundred plus years later our guest speaker Brent Phinney located the remains of one of Saltonstall’s fleet while scuba diving for the remains of the nine vessels of this fleet known to have gone down in the vicinity of Brewer and Bangor. The location of the surviving hull is about midway between the location of the Muddy Rudder Restaurant on the Brewer side and the harbor master’s office on the Bangor side of the river. The discovery resulted in the honor of having this site declared on later US Navy mapping as the “Phinney Site.”

Remarkably timbers, cannon balls, and other defining artifacts remained at the bottom of the river at a fortuitous position near the shore; it was fortuitous because this wreck had largely escaped the severe churning and abrasive nature of winter ice flows of the Penobscot for over two hundred years. This phenomena, Phinney theorizes, likely swept away the remains of the eight other Continental Navy vessels known to have been scuttled.

The wreck is in every sense of the word that, a wreck, for much of what remains is everything below the ship’s original waterline, and this lay largely buried under sediment. There are charred timbers visible that have undoubtedly survived decay because of that circumstance alone. A US Navy survey over the course of four consecutive summers by student divers recovered and photographed many artifacts at the site. Undoubtedly the BHS would be interested in obtaining some copies of those photographs for its own archives.

One of the greatest finds at the site occurred when Phinney himself accompanied the US Navy divers. As an expert on local ship building, be was aware that ship builders often placed a coin under a hollowed out spot on the mast deck before mounting the main mast of a ship. This was considered a talisman. The mast of this wreck had long since been destroyed or displaced but after removing sediments from its original position there lay the oxidized coin. It was later revealed after cleaning to be a 1708 Spanish silver coin. Phinney shared a photograph with the BHS that illustrated the remarkably good condition of the obverse and reverse of the coin. This find remains with all other objects recovered from the site under US Navy stewardship.

A testing of wood samples from the wreck confirmed that this particular vessel was constructed of trees from what is now the State of Maine. Maine, particularly Brewer and Bangor, were responsible for some 161 large wooden vessels during their tenure as premier ship building locations until 1919. In that year, which also marked the armistice of “the war to end all wars,” the building of large four mast sail boats ended with the launching of the last of its kind, the 1000 ton, 210 foot Horace Munroe. The occasion was marked by a dramatic mishap when the schooner slid down its rail faster than expected during the launch, and seamen missed their opportunity to drop anchor. The schooner raced across the Penobscot crashing into the McLaughlin & Company warehouse on the Bangor shore. It had to be towed back to Brewer and repaired.

From 1849-1919 there were four major shipyards producing barkentines, schooners, and other types of sailcraft on the Brewer shoreline. These shipyards changed hands a few times during this seventy year period, but Cooper and Dunning, McGilvery, which was later E. and I.K. Stetson, Gibbs and Phillips, Barbour, and Oakes were among the most prominent. The site of the McGilvery shipyard is currently Brent Phinney’s own steel shipbuilding enterprise. Unlike his antecedents he constructs boats using I-beams and metal plating as well as using modern hydraulics for dry-docking and launching the boats in his yard. His projects are usually limited to 65 feet in length weighing anywhere between 90 and 300 tons.

In days of yore elaborate wooden scaffolding was part of the formula for creating and launching wooden vessels. A wooden rail was lubricated with bear’s grease to insure a smooth glide down to the river’s surface. Oxen and horses were employed in these constructions as well. Seventy five men usually took a year to a year and a half to transform the hand shaped wooden timbers and wrought iron spikes and hardware into a seaworthy vessel. There was no better place for making wooden ships, for Maine is blessed with one of the greatest wood supplies that the world has ever known. Local sapwoods like hacmatack and hardwoods like oak were especially important to boat construction. Local brickyards also supplied brick ballast for these ships.

Phinney has put together a small museum gallery at his office on the Brewer shoreline; here are framed pictures of the Horace Munroe and Charles D. Sanford, which was launched in 1918, among many others. The latter ship also encountered difficulties at its launching sticking fast to the rail during its send off, and the launch was postponed for another day. In 1874, the Claire McGilvery must have displaced much water weighing in at 1329 tons at the McGilvery shipyard. William McGilvery had begun shipbuilding in Searsport, but by 1867 the barkantine Manson was launched from his Brewer site marking decades more of successful ship production.

In addition to photos, Phinney shared some of the tools of the trade of shipbuilding, including an adze, an early rotary measure, and a right-handed axe that had come down through his family by way of a great uncle in Steuben who had been a shipwright. During Phinney’s restoration of the shoreline of his property and while digging footings for a new building on the site, he has uncovered layers of shipbuilding activity below the surface. Among dense wood shavings and sawdust, these layers have produced numerous wrought iron spikes and wood staples once used for joining wood ship timbers. There are also numerous metal files which Phinney reckons were used for sharpening all the hand tools used daily during ship construction.